I was sent to Manus Island by the Internationales Literaturfestival Berlin to write a story for the “State of Refugees” project. This is an edited extract from that piece, published by The Sydney Morning Herald.

In the main square of Lorengau, on Manus Island, people mill about on the street in mismatched clothing, chewing betelnut, conversing, selling produce. There is a long line on pay day at the one functioning ATM in town. Information sheets on diabetes are plastered to the bank wall.

I am met outside of my hotel in the main square by a local woman named Jill*. I’m advised to avoid the port, just a street from where I am staying, because drunks might rob me at knife-point. I’m advised to travel around the island in the company of a local to be safe.

A melted, crumpled building sags over the footpath on the main road. This used to be a supermarket owned by Chinese migrants before it was burned down with 10 people inside, including women and children. The rumour in town is that the fire was deliberately started by “out-of-towners” to cover up murder.

Jill and I walk through the town market which has a brand new roof, one of the few infrastructure projects provided to the island by the Australian government as repayment for housing Australia’s unwanted boat people. Women with tribe-distinguishing tattoos on their foreheads sit on plastic mats selling fresh produce: eggplants, bananas, beans, stone fruit, cabbages, bok choy, coconuts, dirt-covered potatoes, sago palm.

Jill picks up a small green nut. “Green gold,” she says.

Jill worked in the Manus Island detention centre for five years. The Project, as she calls it (identified as “The” because there have been so few projects on the island), brought jobs and some financial prosperity to Manus Island.

“There are no jobs in Manus. Usually finding employment in Manus is about who you know. We call it the wan-tok [one talk] system. You only need to talk to one person to get the job. But the Australian organisations weren’t affected by nepotism,” she said.

According to Jill, the prosperity The Project brought the island meant the local people became a centre for the betelnut trade, the green gold. The new wealth of the locals attracted people from other islands for trade and business opportunities. Suddenly they had street vendors and the market was full of strangers. The increased wealth brought greater wealth disparity on the island, which brought crime and theft and conflict.

“Even we feel scared walking at night. It didn’t used to be like that,” Jill said.

If the stand-off at the Manus Island detention centre rests upon an argument over safety, there are clear signs that there are dangers in the community regardless of whether or not you are a refugee.

At the two other supermarkets on the island, many of the shelves are empty. Since the razing of the Chinese-owned supermarket, the demand for food has stripped the cupboards bare. On this island it is easier to get soft drink than bottled water. There has been a delayed shipment to the island which means there is an island-wide fuel shortage. The electricity is being cut off during the day to save energy.

“Life is hard in Manus,” Jill says. “But these refugees are given everything. Food, housing, cigarettes, an allowance. What do we get?”

I learn that there are many locals who feel the same way. In their corrugated iron housing, is it any wonder they are resentful of the million-dollar facilities housing the asylum seekers?

From Jill and her friends’ perspective, the problems all started when the refugees were forced to live in the community.

“This was not the Manus people’s decision. The refugees want to go to Australia. They don’t want to stay in Manus. This causes problems for everyone here. We don’t want them here if they are unhappy. Those men have been here for four years and they need to be resettled somewhere else.”

* * *

The Australian and Papua New Guinea governments are determined to relocate the refugees and asylum seekers to two new settlement locations on the island. East Lorengau Transit Centre (ELTC) was built three years ago and houses processed refugees. Hillside Haus accommodates those who have been given negative refugee assessments. There is a third site, known as West Lorengau Haus, but no one in the community knows where it is.

Gulam* is a short man from Bangladesh in his 40s with chipmunk cheeks and a combover. He says his hair started to go grey when he arrived in Manus, a stress-related fade. He moved to ELTC from the Manus Island Regional Process Centre (MIRPC) in July 2015.

“They told me I would have more freedom, more opportunity, more money there. But it was all lies.”

Gulam sleeps in a cramped room that barely fits two bunk beds with three other men. There is no air conditioning so it is too hot to stay inside the room during the day. Twelve people share one kitchen and one toilet. At the front entrance to the centre there is a boom gate manned by Australian and PNG security guards. An easily scaleable fence surrounds the perimeter. The refugees are not allowed visitors. It’s another detention centre, another prison, just with a different face.

Every refugee I meet in the community in Manus has a story of violence at the hands of locals.

“On the road to market, we pass through the jungle and people hide there like tigers and attack us. They threaten us with machetes and demand money, cigarettes and our mobile phones. I have been attacked and robbed four times. They think we are rich,” Gulam says.

But most of the refugees appear rich only in comparison to the poverty of the local community. In reality their smart phones are paid off week by week. Those refugees in ELTC receive 100 kina ($A40) allowance per week and a small amount of food.

“With that money I must buy medication, phone credit and groceries. And cigarettes. Before Manus I didn’t smoke. I became addicted to the free cigarettes in the camp,” Gulam says.

“When we lived in the detention centre we were given free cigarettes which the locals expected us to share. But they don’t realise that the people living in East Lorengau don’t get free cigarettes any more,” says Nasir*, a young Rohingya man.

Most of the physical dangers for refugees appear to be a product of wealth inequality. Impoverished local young men, drunk or high, picking on refugees as easy targets. There are only a few refugees who have jobs in the community. Nasir is a truck driver but he can’t find any work because there aren’t any jobs on the island. Gulam sells packaged lunches at the market in town for income, but he thinks it’s too dangerous to leave the centre to continue his work. The men don’t feel like they belong in Manus, they feel like unwanted outsiders.

“The local call us illegal immigrants. They tell us to go back to our own countries. We tell them that your government brought us here,” Gulam says.

Without work, without purpose, without family, life becomes unbearable and some men resort to alcohol and marijuana to dull the pain. In town I see an intoxicated Iranian man stumbling across the road shouting belligerently at passersby. Behaviour like this makes many locals believe the refugees bring the violence upon themselves.

In the MIRPC, one of security’s jobs was to keep people alive, to cut people down when they tried to hang themselves. The danger of East Lorengau is that there isn’t enough security to prevent the men from hurting themselves. There have been two suicides in the community in the past three months.

* * *

It is clear the trust between the refugees and the locals has broken down. They are suspicious of each other, they are critical of each other. Despite this tension, there are many friendships and relationships between locals and refugees.

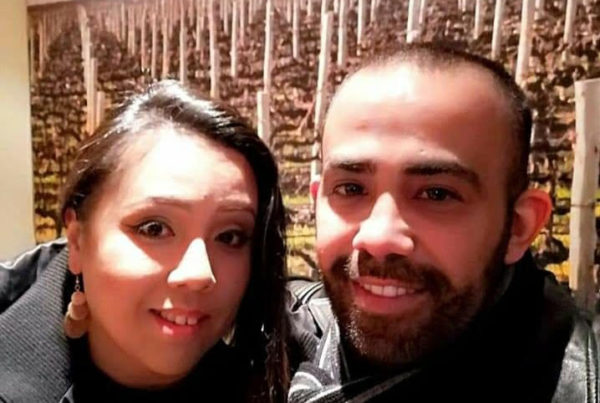

Umsal* is a handsome man with Bollywood actor features. He is from the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, a vast jungle of tigers and snakes and elephants. He left the MIRPC when the services ceased and the conditions deteriorated. But he avoided the transit centres and stayed with a local woman, Fanny, with whom he is in a relationship.

“I do not enjoy Manus. Life is a struggle. It is a struggle for everyone,” Umsal says.

“That’s why we found each other,” Fanny* said. “We were both struggling.”

“We are not free. I’m worried about attacks all the time,” Umsal says.

Fanny accompanies him everywhere. She thinks it’s too dangerous for him to go anywhere alone. Fanny’s family support them and their relationship, but they are worried about him leaving. Umsal was given a negative refugee assessment and his residency status is now uncertain. As far as they know, he could be deported at any moment.

Locals express concern about relationships between local women and refugees whose future on the island is uncertain, of pregnancies with a high likelihood of abandonment. What will happen to the children of these refugees when their fathers are relocated to another country?

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton has tried to use the existence of relationships between local women and refugees and asylum seekers as evidence of community harmony. However, these relationships are rare and uncomfortable circumstances, which usually cause tension in the community. In the case of Umsal, the uncertainty of his future is disruptive and upsetting for everyone involved.

“I tell him not to worry about the future. He should live for today,” she said. “But he gets very worried.”

“My life is over,” he mutters to me without Fanny hearing.

* * *

Not everyone benefitted from the employment and prosperity the Project brought to the island, and not everybody was willing to work at the detention centre. Some locals have staged protests against the centre, brandishing signs that read “Manus Alliance Against Human Rights Abuse” and “Australia Don’t Abandon Your Responsibility”. Some of these human rights activists, such as Ben Wamoi, fled the island after receiving threats from the police.

The MIRPC is a poisoned chalice, bringing with it societal discord and a negative international reputation that the people of Manus are keen to shed.

“The media has portrayed us as bad people but Melanesian culture is friendly, family-orientated. We like to smile, enjoy, be happy,” Jill says.

The international media’s portrayal of Manus has led to a deep distrust in journalists and foreigners that has created a police-state-like monitoring of association. Jill does not want anyone in the Manus community to know that she is helping me write this article because she is worried that she will be reported to the authorities.

The closure of the MIRPC has left most of the local detention centre staff without jobs. Many of the unemployed hit the streets on a Friday night, spending their severance pay on alcohol and betelnut, perpetuating the cycle of poverty and violence. Jill is hoping for employment with the new resettlement program but nobody knows when this stand-off will end.

I meet the mayor of Lorengau, Ruth Mandrakamo, by chance in a car to the airport.

“The Australian government sealed the main road, assisted with some schools, refurbished the police station, and upgraded facilities at the naval base,” she says. “I am envious of the aid they have given us over the years but it means we feel obliged to help Australia. The decision to establish the detention centres was top down, straight from the prime minister. There was no community consultation.”

*Names have been changed