In the current political climate of secrecy that envelops Australia’s treatment of people seeking asylum in our country, it is rare to hear first-hand accounts from within Australia’s detention centres. The small amount we do hear usually comes from whistle-blowers breaching contracts and deeds of confidentiality to speak out. Almost never do we hear from the people detained inside our centres.

Ravi is one man willing to speak about what happened to him (note I have not changed his name to hide his identity). After travelling to Australia from Sri Lanka by boat, Ravi was detained in the Nauru Regional Processing Centre and then Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation for over three years. Towards the end of 2015, Ravi was permitted to live in the community on a bridging visa. He has since published a collection of his poems and artworks composed from within our detention centre system. The other night, I had the pleasure of joining Amnesty International and Ravi at Berkelouw Books in Paddington to launch his book ‘From Hell to Hell’ and to discuss his time in detention.

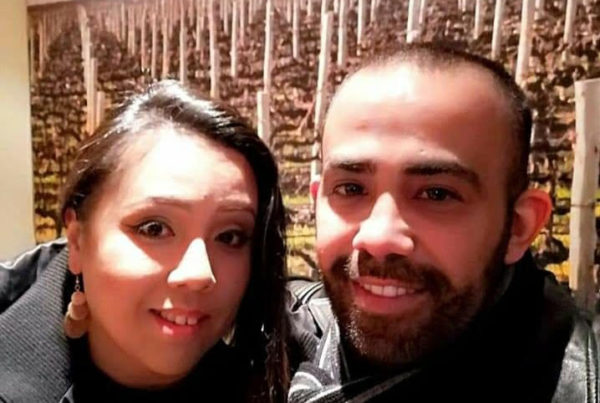

If you have read my book, ‘The Undesirables’, you may already know Ravi as the charismatic character Devkumar. Ravi was one of the first men I met in Nauru. He approached me in my first few days and asked me to arrange a cricket match. From there, I established the first recreations program in the Nauru Regional Processing Centre. Ravi was an organiser and, at times, a leader. He could be charismatic, but he could also be overpowering. He claims he was accused by Wilson Security guards of being a ring leader of protests and violence. He liked to maintain an immaculate appearance in a centre where everyone looked dishevelled, even the workers. Seeing him in Paddington the other evening, dressed in flash shades and a maroon shirt and looking like a king pin, showed me that in some ways Ravi hasn’t changed.

When speaking to the crowd that night, Ravi referred to the Nauru RPC as a human dumping ground: a place where dreams are shattered. He believes he was treated well by some workers and horribly by others. He criticised the Salvation Army as an organisation for not acting in a humanitarian manner. He assessed Wilson Security guards individually and alluded to acts of violence committed by the nastier men. He praised the healing powers of Australian Panadol, the most common form of medication provided by health services in detention.

“I didn’t know that Australian Panadol was so strong it could heal all problems.”

I didn’t agree with all of Ravi’s assessments of Nauru, particularly his claims regarding the food. However, when I asked him about men detained in the camp acting violently, Ravi made us all reflect on Australia’s expectation that refugees and asylum seekers should be grateful for our protection and behave themselves.

“If you were locked in a box, what would you do?”

‘From Hell to Hell’ is by no means an easy read. Ravi pens his poetry in English, his third language. The content is dark and draining. Yet, this collection of creative content is a testament to the mental anguish people suffer while incarcerated indefinitely inside our detention centres. Ravi has acted courageously to publish this book and to speak publicly about his experiences. Most men I speak to who were detained in Nauru prefer to remain silent and suppress their trauma. A few will speak under cover of anonymity, fearful that any kind of public outcry will risk their case for refugee status. Considering our government’s vindictive policies towards people arriving by boat, I believe they have cause to be afraid. When refugee voices are so often silenced in the Australian debate regarding asylum seeker policy, Ravi’s willingness to speak openly about his time in detention is invaluable.

At the end of the talk I asked Ravi how it felt to be free.

“I am not free,” he replied. “Not until that human dumping ground is closed.”

‘From Hell to Hell’ was produced by Writing Through Fences, a writing group made up of people who are, or have been, directly affected by the Australian immigration industry and a small number of writers who are residents or citizens of Australia. If you would like to purchase the book, please contact them directly.