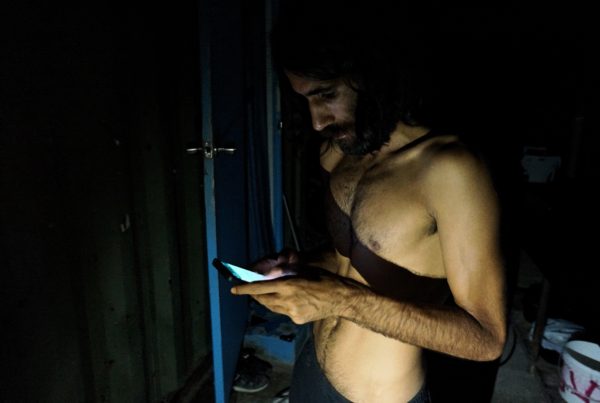

I met Robin de Crespigny just prior to publishing The Undesirables: Inside Nauru. From our very first meeting she acted as a mentor to me and she continues to be a dear friend and a source of inspiration. She has generously allowed me to publish this excerpt from her award-winning book, The People Smuggler: The true story of Ali Al Jenabi the Oskar Schindler of Asia. The book is about one man’s flight from Saddam Hussein’s torture chambers, and his country, Iraq. It is an international odyssey through the shadow world of fake passports, crowded camps and illegal border crossings, living every day with excruciating uncertainty about what the next will bring. If you haven’t read this book, I encourage you to purchase it. It’s an incredible read. **** GRAPHIC CONTENT WARNING ****

They attach the electrodes to my back, tongue and genitals, and the current surges through my body like fire in my veins and I stiffen and shudder.

I have no idea how much time has gone by but they cooked me until I passed out, and now I am waking back in our cell. I am grateful for the familiar surroundings and the sight of Akram sitting beside me as I lie shivering on the floor. My head throbs so violently my vision blurs, and a sharp pain pulses through my limbs. The feeling of paralysis is what really scares me but Akram is reassuring.

‘Better for you to stay asleep,’ he says as he spreads my blanket over me. ‘The numbness will go. In a few days you will be back to normal.’

‘Did they get what they wanted out of you?’ I ask, wondering how many goes it takes before you go crazy and tell them anything.

He clasps and unclasps his hands and for the first time I notice that Akram has no fingernails. ‘They did,’ he says after a pause, then goes on haltingly. ‘I stayed out of politics. I taught ten- to twelve- year- olds at a respected school. We talked about many things. I was good friends with the other teachers and the children. I loved my job.’

‘You don’t need to tell me,’ I say quickly but he seems to want to go on, perhaps to justify so many nights of soundless crying when his body shook so vigorously that neither of us could sleep.

‘I’m just a normal Muslim but I wanted to improve my under- standing of my faith and to be a better teacher, so I borrowed a book on Islam from the library. One day when I was walking home the secret police picked me up. I happened to have the book with me, so they took me in and beat me because they thought I must be part of some Islamic movement. Saddam had purged the Communists, now he was after the Islamics.

‘When I refused to admit to something so ridiculously false they brought out their tools of trade and worked on me for so long I finally confessed. But that wasn’t enough. They wanted names of others. They tortured me until I begged them to let me die, but they wouldn’t. They waited for me to revive so they could keep on with it … until I told them all the other teachers in the school were part of an Islamic movement too.’

He pauses, hanging his head and drawing circles in the dirt with his pulpy fingers. ‘So they picked up the twelve other teachers. They tortured them all, then executed six of them.’

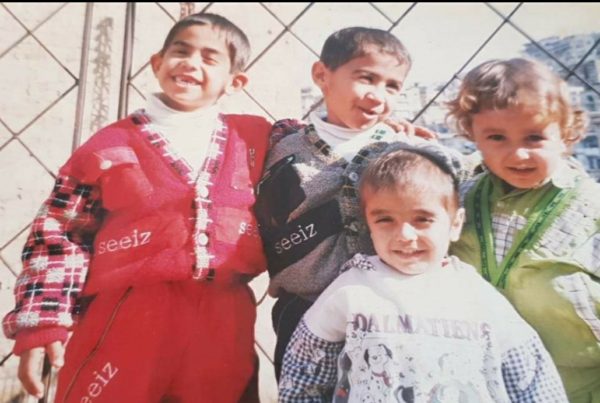

The dormant political man inside me stirs and I understand why people give their lives to rise up against a dictator. I remember my father’s voice and I wish I could tell him I am at one with him now. I want to cry out, ‘Saddam is a bastard,’ but if I do I endanger all the men in my cell. So I coil my legs to my body and bury my head in my knees and I think of Akram’s pain and of my brother Ahmad and my own fried brain and I weep silent tears of rage.