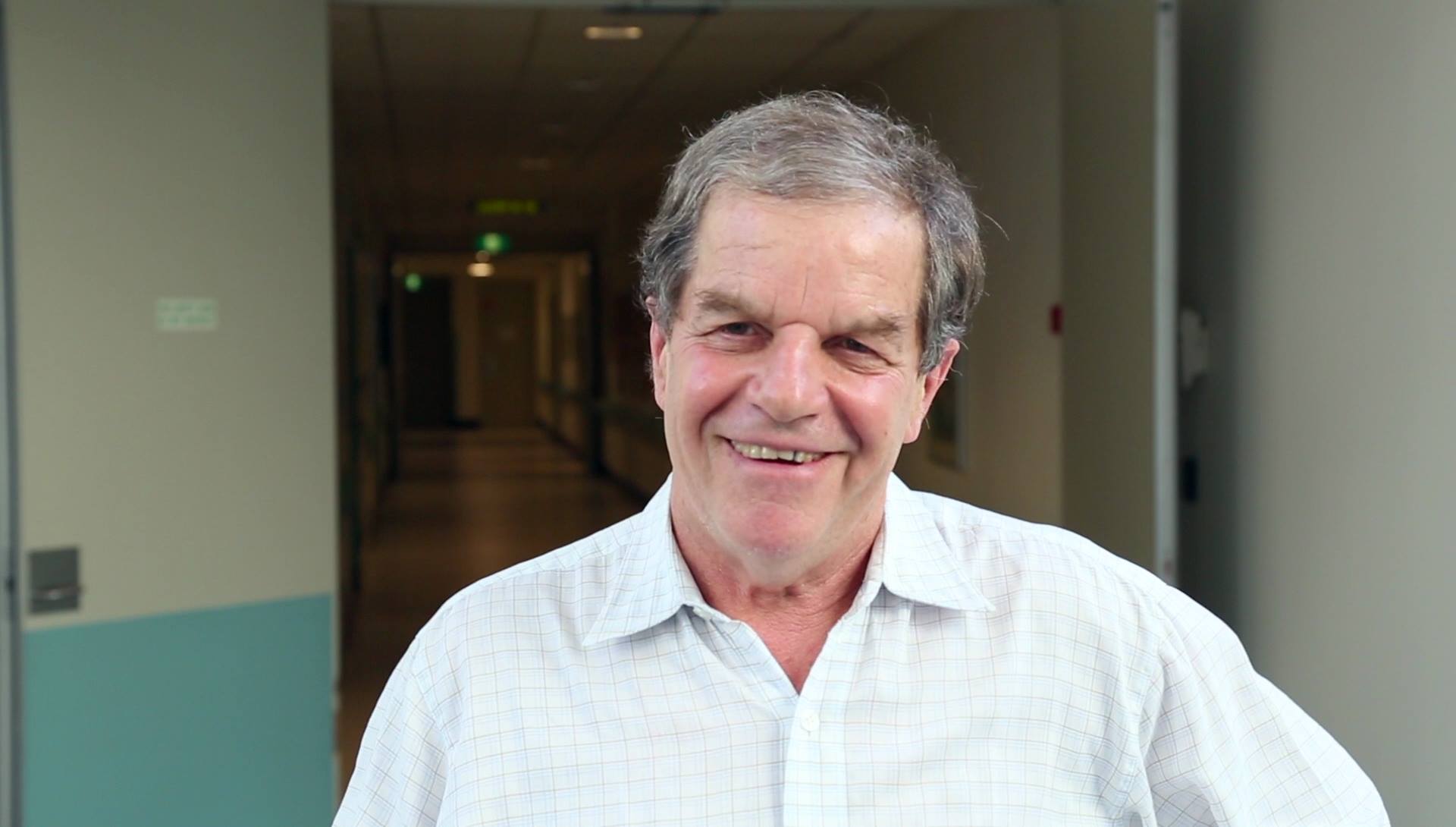

My father, Professor David Isaacs, was working with refugees long before I went to Nauru with the Salvation Army. Dave, a consultant paediatrician in Westmead Children’s Hospital and a clinical professor at the University of Sydney, has run a refugee clinic at Westmead since 2005. Just over a year after I returned from Nauru, Dave was invited to visit Nauru as a specialist paediatrician by the International Health and Medical Services. He has since spoken publicly about his experiences in Nauru. This is an article he wrote that was first published in the Sydney Morning Herald on February 29, 2016.

If I liken the immigration detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island to the US facility on Guantanamo Bay, even passionate advocates for those seeking asylum such as human rights lawyer Julian Burnside dismiss my concerns: “Oh we’re not as bad as that.” I will argue that we are indeed as bad as that, possibly worse.

Many people fleeing persecution to seek asylum have been subjected to psychological trauma in the countries they are fleeing and in the often highly traumatic journeys they take to reach ‘freedom’. However, people seeking asylum who are subjected to prolonged immigration detention are significantly more likely to suffer severe mental health problems than people seeking asylum who are not detained. Furthermore, the incidence of mental health problems increases with duration of incarceration. The United Nations defines torture as “…any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions”. Since prolonged detention without trial is unlawful under international law, Australia’s immigration detention policy clearly fulfils the key elements of the UN definition.

Arguably what makes Guantanamo so bad is four things: lack of due process for imprisoning people there, lack of accountability (limited information, no transparency), indefinite imprisonment without due process (seemingly arbitrary legal processing, lack of clear end- point to imprisonment); and severe physical and mental maltreatment. Nauru and Manus share the first three characteristics with Guantanamo. Nauru and Manus, like Guantanamo, are ‘black sites’, out of sight and mind of the public, shrouded in secrecy, with severe restrictions on reporters. The Australian Border Force Act means employees including doctors, lawyers, teachers and guards who report the truth face two years imprisonment. Yet, for an Australian offshore detention policy to be successful in deterring people-smuggling, the stated intention, none of these four things are necessary. Therefore, even if you accept the Government justification for the Australian asylum seeker policy, the current treatment is unethical.

Guantanamo is arguably worse in one respect: we know men are systematically tortured physically using techniques like water-boarding. However, Nauru is worse than Guantanamo in one hugely important respect: it includes children. When we surveyed Australian paediatricians, over 80% said immigration detention of children is child abuse. Successive Australian Governments have outdone the US Government in cruelty by torturing and abusing innocent children, all with the immoral aim of deterring other innocents.

Furthermore, those imprisoned on Manus and Nauru are not terrorists; indeed, they are not guilty of any criminal offence, since seeking asylum is not a crime. Although the occasional innocent man was interned on Guantanamo, most knew what to expect when they went to war. In their autobiographies, Primo Levi and Nelson Mandela both astonishingly attempted without rancour to understand the motives of their captors; when they took up arms to fight injustice, they both knew the consequences if caught. On Nauru and Manus Island, in contrast, the injustice is being perpetrated against the very people seeking asylum. There can be few worse things than to be imprisoned unjustly and kept there indefinitely without right of appeal. Australia tortures innocent men, women and children who come begging for mercy. No wonder we are reviled internationally.

When I worked on Nauru in December 2014, the predominant emotion was of utter despair and hopelessness. What would you do if you were imprisoned unjustly and indefinitely without right of appeal? In the current culture of victim-blaming, if you get depressed and self-harm or attempt suicide, you are accused by the Government of seeking preferential treatment. If you subsequently kill yourself, you had pre-existing mental health problems. If you get angry enough to riot, you are accused of violent ingratitude, with no mention of the extreme provocation that causes normally placid people to get angry enough to resort to violent protest.

Gillian Triggs and the Australian Human Rights Commission have tirelessly and courageously exposed the harms done to children in immigration detention. The harm is also to adults, of course. But the very term ‘human rights’ implies an obligation, which risks being somewhat confrontational. Australia’s reprehensible treatment of people seeking asylum is as much a question of human decency as human rights. No civilised country should behave like this to fellow human beings. We treat refugees with respect and generosity. We treat people seeking asylum with contempt and cruelty. We talk of showing compassion, and in the same breath tell the meek to go back to where they came from. Australia is traditionally the land of the fair go, but in the words of president of the Australian Medical Association, Brian Owler, current asylum seeker policy is tearing at the moral fabric of our society. We, the public, need to prevail on all our politicians to listen to our pleas to find a new moral direction. Please help us re-discover our soul.