I spent three days with Arman* recording his story from every angle. As English is not his first language I have reworked some of the material, so while it is not always exactly his words the events are entirely his.

“I saw a man screaming for his baby son, another howling for someone to help his mother who struggled amongst the waves to reach the boat, only to be flung off before she could take hold. I know that he can swim, I knew him, but he is paralysed by the fear. He clenches his hands and cries out for help like a child in despair. No one was paying attention to anyone. Everyone was a knife edge away from their own death.”

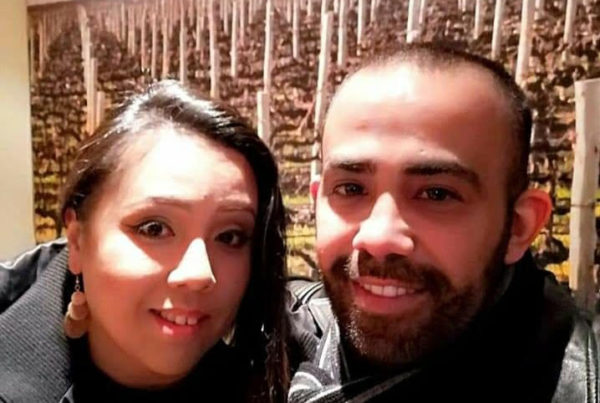

Arman speaks quietly, a gentle, 30-something Iranian man whose boat, carrying 250 asylum seekers and refugees bound for Australia, sank just 40 nautical miles off the Java Coast of Indonesia in December 2011. He was one of only 47 survivors.

“You should have been there, you should have seen it, just water everywhere with waves five metres high, coming from every direction. You are sitting on the bottom of the boat which is upside down and rolls over each time a wave hits,” Arman continues. “As it rolls everyone is flung off or dragged under and swept inside the vessel where broken bodies are tangled amongst ropes and lumps of timber. Each time it comes up again there are less people clambering to get back on.”

Arman and I are sitting on the veranda of a café in an old colonial house near the gateway of the Parramatta Park in Sydney. I can remember the media coverage at the time and I try to imagine the horror of dying in the ocean, alone or with loved ones floundering around you. But only the statistics seemed real: another 200 deaths to be tallied against the government of the day.

I am pulled from my reverie by the arrival of our coffee and note the irony of sitting amongst the tranquil beauty of the park while hearing the horror of Arman’s experience. How many of us are truly able to empathise with the desperation and courage it must take to embark on a journey such as this? Especially when you are already traumatised by what you are leaving.

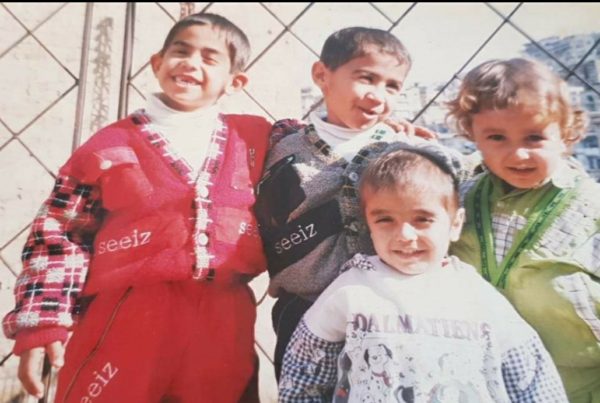

In 2009-10 Arman had participated in the Green Revolution in Iran, which rose up against the allegedly corrupt election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who was intent on imposing an Islamic State with Sharia Law on his people. When his close friend was executed, Arman escaped a similar fate by fleeing with the hope of reaching protection in Australia.

* * *

Arman tells me how he and the other asylum seekers – mostly Iranians and Afghanis, but also Syrians, Iraqis, Sudanese and others – were happy when they first saw the boat which they believed would bring them to Australia. Usually smugglers use smaller fishing boats but this boat – the Barokah – was a huge square-shaped hulk that looked solid, though it was designed to carry produce, not people.

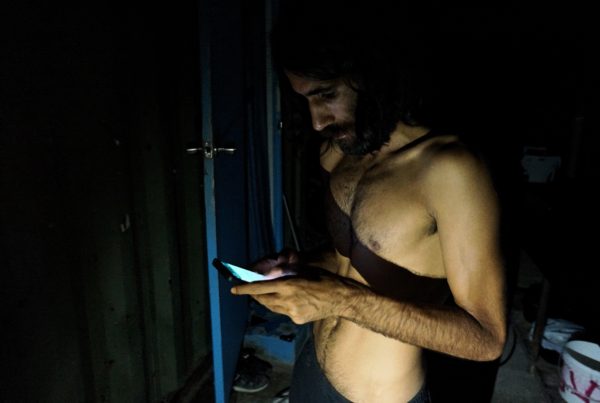

But once the boat was full they could see there were far too many people, but nobody wanted to get off. Most of them could not go back to their own countries. Some, like Arman, had tried to get a boat many times but failed and others, their three-month visas having expired, had been waiting in Indonesia for years struggling to stay alive in urban areas, where 72 per cent of asylum seekers hide. They have no work rights so most of them live on their wits in extreme poverty and deprivation.

“The families were on the upper deck with a tarp tied above them for protection,” Arman says. “I was on the lower deck with over a hundred, mainly single, men.

“There was a long table bolted to the floor for preparing produce, with a narrow walkway around it and two windows about one metre square, opening onto the sea on each side. I don’t know why, but the crew came in the night and nailed up the ones on the left with canvas. Maybe to stop the wind blowing water in. A lot of people were packed together like sardines under the table but I grabbed a spot on top of it near one of the open windows.

“The engine ran well and a young Indonesian crew regularly attended to it, but the sound of it was deafening, and the smell of diesel mixed with vomit on the floor from people who were seasick was terrible. They should have put their heads out the window but probably they were scared of the sea.

“A group of us stayed awake all night chatting, excited, afraid; we had heard lots of stories of boats sinking. There was a Pakistani guy on our deck who had sunk, swam to shore and tried again five times. No one knew how many of his family he might have lost but he was now a little crazy. He continually walked around checking things, and tapping the walls. He was very anxious and angry, and shouting at people to be careful, not to all go to one side or the other and unbalance the boat.

“It was so crowded people had to sleep around the engine, so at dawn some of them began going quietly upstairs for fresh air and to watch the sunrise. The crew, just young boys, were not controlling who went where and the Pakistani must have exhausted his rage and fallen asleep.

“There was a kitchen stocked with plenty of watermelon, eggs, and noodles so when we saw the sun rising we decided to have some food, then try to sleep. We stood by the window looking out while we ate and for the first time I saw some flying fish.

“When I got on the table and pulled my bag behind my head to lie down, the boat began to roll. I was thinking the extra people would have made it heavier on top and wished the Pakistani was at hand to yell at them to stop unbalancing it.

“I felt the boat tip with the waves to one side then to the other, then this side, then that. But suddenly it didn’t come back. I was thinking: ‘We have rolled too far. We are going into the ocean.’ It happened in a second but I knew we were gone.”

* * *

“The boat was shaped like a box and had rolled onto its side with the water blasting in through the two uncovered windows, which were now below us. It made a terrible sound, louder than the engine, which began to splutter and stop.”

In a flash around a hundred mostly sleeping people were thrown through the air, smashing into walls, the edge of the table, flying objects, luggage and each other, splitting heads and breaking limbs as they plummeted into water that belched up through the only exits with the force of the Indian Ocean behind it.

“In that moment I took my left hand like this,” Arman is standing up in the café reaching for the ceiling, and I have forgotten where we are. “I grabbed the edge of the table which was the only thing that saved me. Otherwise I would have slid off it and into the mass of bodies swirling below me. I hung there while people were falling down like from the sky, as the water rushed up to meet us.

“Some people were getting out but mostly they were entangled and clawing at each other, screaming as they tried to get through the bodies stacking up and blocking their escape. They grabbed anything and if it was your clothes you couldn’t get away. Maybe that is why I later saw a dead woman in the water completely naked. Perhaps it was the only way she could get free but it took too long and she drowned anyway.

“The windows on the other side were now above us but they were blocked with the canvas. As the water pushed us higher I saw a man swim and somehow punch and rip it out. I let go of the table and reached both hands up, and the water from below must have blasted me out into the ocean.

“I came to the surface with my lungs almost bursting. It only felt like five seconds since I had shot out the window but already the upturned boat was now over 500 metres away. I was surrounded with dead bodies and people screaming and thrashing in the sea. Some were hanging onto floating wreckage, or the box that the life jackets were in. I had seen the jackets on the boat when we embarked, but they were never distributed.”

* * *

My mind jumps to the very young, inexperienced crew. They might have grown up on fishing boats in coastal waters, but were unlikely to be capable of taking charge of 250 foreign passengers who spoke different languages, or of mastering the open sea when they turned from the coastal waters of southern Java towards Christmas Island.

Smugglers employ young boys as crew because if they are over 18 and caught by the Australian officials, they are charged with people smuggling and imprisoned for five years. Consequently they use boys as young as 14 to avoid them being assessed and imprisoned as adults.

When Australia “turns back boats” – even when we replace the one we intercepted – they are returned with the same captain and “child” crew.

* * *

When I first heard Arman’s story I was concerned it could justify boat “turn-backs”, in the name of saving lives at sea. But it was 27 November, 2015 and I had just heard about a boat carrying 16 asylum seekers who had been found stranded near West Kupang in Indonesia. They had made it to within 200 metres of Christmas Island when the Australian Navy towed them back out to sea, after which they had disappeared.

They had been put on another boat but with only enough fuel to reach Indonesia, as is repeatedly the case under our tow-back policy. Any divergence from the route or bad weather could leave the boat lost in perilous seas. The Indian Ocean is wild and dangerous, especially in late November at the beginning of the monsoons.

If deaths at sea were truthfully our concern, with the journey from Indonesia being such a treacherous one, we would be relieved when the boats reached Christmas Island safely. Instead, we force people seeking asylum to risk the journey again in reverse, crossing Indonesian waters in the same ocean where the tragedy of the Barokah occurred.

After the turn-back policy was first introduced by John Howard as Operation Relex in 2001, two boats sank during the return process. The engine of another died 400 metres from Indonesia’s shore leaving 88 passengers to swim or wade to the beach. Three reportedly drowned.

Another one exploded, killing two of the 160 asylum seekers on board with many others, including Australian officials, injured. Asylum seekers are often so terrified of being sent back to detention or refoulment – being returned to their country of persecution – they will do anything to prevent it, including harming the boat and themselves.

* * *

While we squabble about shortage of funds for improvements to education and health there appears to be no limit to what can be spent on turning boats back. While we spend our fortunes on stopping people from exercising their right to seek asylum here, many other countries, especially now with the Syrian crisis, are spending that kind of money on taking them in.

The Abbott Government set up Operation Sovereign Borders in 2013 at a cost of around $400 million a year and all matters concerning asylum seeker activities went underground in the name of “border security”.

The Australian public was first alerted to the use of orange, capsule-like lifeboats as an alternative to tow-backs when one was found on a remote shore of Indonesia’s West Java. About 60 people had emerged and been seen dirty, distraught and running into the jungle, where three of them died after they wandered lost and terrified for several days.

In March 2014 the third group of asylum seekers was turned back in one of these strange capsules, claiming they were tricked into boarding by being told they were going to Christmas Island. It ran aground in huge seas 30 metres from the Indonesian shore. Another few hundred metres out and it could have been a disaster.

Even though these lifeboats were fully enclosed and submersible, if they hit the five-metre waves that the Barokah encountered, there is every chance they would run out of fuel. With the veil of secrecy that surrounds the turn-back operations, we may never know if any of these lifeboats ended up with its passengers dying a terrible death at sea, sealed in a hot, dark, suffocating capsule reeking of seasickness.

In March 2014 the Abbott Government tripled the amount of money spent on these orange capsules to $7.5 million, each costing between $46,000 to $200,000, and abandoned after one use.

According to documents obtained by Fairfax Media, another $5.7 million was spent on technology to locate “security threats” on the water before they reach Australia. Another $16.8 million was spent on six months usage of the naval vessel, Triton, and a further $25 million for the armed patrol vessel.

But this was only the beginning. With our current regime of “deterrence”, which punishes those who arrive by boat after 1 July 2014 with incarceration on Manus Island and Nauru, official government figures show the total costs of detention and compliance-related programs for these asylum seekers will be $2.30 billion in 2015-16.

This is an extract of an essay originally published at Right Now. Follow the link to read the full-length original essay.

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Robin de Crespigny is a Sydney filmmaker and the author of the award-winning book The People Smuggler.

Editor: Erin Handley

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its funding and advisory body.

This essay is part of the Right Now Essay Series. To read more essays in the series, click here.