Ashkan contacted me online in December 2014 with a simple message.

“Hi Mark. When are you coming to Indonesia? I am an Iranian refugee in Indonesia. Please contact me. Thanks.”

He asked me if I could visit him in Jakarta and just a few weeks later I had the opportunity to accept his invitation when I travelled to Indonesia in January 2015.

Ashkan’s apartment block is located in central Jakarta on a busy main road. The grimy, pink building towers over me and the nearby infrastructure. Ashkan meets me in the ground floor shopping foyer of the apartment building. He is a young man who seems eager to please. I ask him why he invited me to Jakarta.

“I heard from an Australian friend on Facebook that you had written a book about refugees so I contacted you to tell you about the situation of refugees in Indonesia. Many Aussie people care about refugees in Manus and Nauru but not about us.”

He speaks quickly, as if he has been starved for conversation, and barely waits for a reply before talking again.

“The Iranian regime is the devil. They do not care about religion. All they care about is money and power, yet religion is their main weapon against people. All the misery of the Iranian people is for the wealth of oil and gas in the south of Iran.”

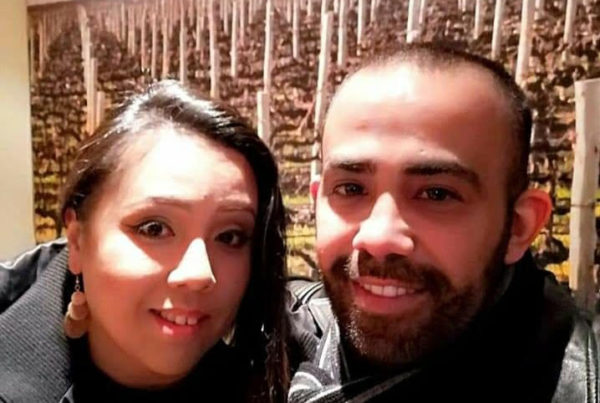

He lives with his wife and her sister in a cramped apartment that doesn’t seem big enough for the three of them. They say their ‘salams‘ to me from the doorway. We take our conversation to the complex’s swimming pool area.

“I did nothing wrong in Iran,” Ashkan says. “But because there is no justice and due to corruption one needs to seek justice themselves and they may face even execution seeking it. I did many things in Iran only to achieve my rights and I faced many problems I am not able to share.”

Like all the other asylum seekers in Indonesia, Ashkan is waiting for resettlement. He fills his days however he can.

“I practice at the gym inside the apartment about 3 to 4 hours per day, 5 days a week. I surf on the internet, practice English, and read books. I used to teach the refugees at a learning centre two days a week for free. I go to church every Sunday morning and I am doing research about Christianity. I help a TV channel called nanogole sorkh in United Kingdom and translate their interviews for free. I go to the traditional market once a week early in the morning to buy cheap fresh food. I would like to attend some welding inspection courses so I can find a job easily when I am resettled but these international courses are too expensive. I talk to a few Australian friends I have on Viber sometimes and they help me a lot.”

We are momentarily joined by a squat, muscly Indonesian gym buff. It is a strange interaction between them. Although Ashkan introduces the Indonesian man as a friend, he doesn’t look entirely comfortable with his company. I feel as if Ashkan is pretending to socialise and his heart isn’t in it. When the man leaves Ashkan looks tired.

“I feel like a prisoner here. My wife is so depressed and misses her family a lot. I try to do my best not to waste my time here but still I feel always sad living in this shoe box.”

I leave Ashkan with promises to stay in touch.

* All interviews have been edited and names and details have been altered to protect identities.