First published by http://johnmenadue.com/

Over the past decades of asylum seeker policy in Australia we have heard many justifications for a strict deterrence policy: border protection, to save lives at sea, ‘no advantage’ for queue jumpers, smash the people smugglers’ business model, and, of course, ‘we decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come’.

At the same time, public debate fostered by mainstream media and by Australian politicians continually refers to asylum seekers by terms such as ‘illegals’ and ‘queue jumpers’, terms that we must continually reject as they have no legitimacy in Australian or international law and aren’t representative of the global view of asylum seekers. Those who control the public discourse have created a confused and purposefully misleading national discussion that shadows the truth and promotes anti-asylum seeker sentiment.

This was recently made clear to me with the recent publication of my novel, The Undesirables: Inside Nauru, and the subsequent media space I have had the privilege to occupy. I was faced with a multitude of different arguments that rarely aligned but all came from a similar source: propaganda. The main issue most journalists wanted me to address was the idea that a deterrence policy does stop asylum seekers getting on boats to come to Australia, and hence, the government is saving lives. It seems that when a person speaks out on humanitarian grounds, with the knowledge and conviction to say that these people aren’t illegals, terrorists, threats to our security, the debate focuses on ‘saving lives at sea’.

First and foremost, I don’t believe that this policy is about saving lives. If this policy is about saving lives at sea, and not the border protection threats Scott Morrison cites in his press releases, why aren’t we championing this policy to the world as a humanitarian achievement? Why is the policy so heavily criticised by international organisations such as UNHCR and Amnesty International? Why has the Australian government banned Australian media from entering the camps? Why are we not allowed to know how many boats the government has turned back to Indonesia?

Let’s say that this policy does stop asylum seekers taking boats to Australia. This doesn’t necessarily save lives and doesn’t solve any global issues with asylum seekers; it merely shifts our responsibility for protecting asylum seekers, a responsibility assumed by signing the United Nations Refugee Convention, to another part of the world. It means those asylum seekers originally facing persecution now face a very bleak situation in Indonesia, a country that has no such obligations to processing refugees. Asylum seekers will still need to flee persecution and will still need the help of people smugglers to facilitate their escape because there are few ‘correct channels’ of migration, if any, available to many of them. I asked the men I worked with in Nauru why they didn’t come to Australia by the ‘correct channels’. Such a question was an insult in the camp.

“You show me the Australian embassy in Afghanistan. You see if a Hazara man can go there without being shot. If you go to the Australian embassy they ask you why you want to leave. If you say you have a problem, they say it is not enough. Many people have tried. We cannot go to our government and ask for visas. We are not even allowed to study in Afghanistan. How do I apply for a visa to Australia when my government wants to kill me? If you want to go to the United Nations office in Quetta, Pakistan, it is in a dangerous area. People recognise Hazara faces and they target them easily. If you go there, you have to stay for a long time and it is dangerous. Maybe you will be targeted. You think we would leave our homes if we didn’t have to? You think I’d leave my family if I didn’t have to?”

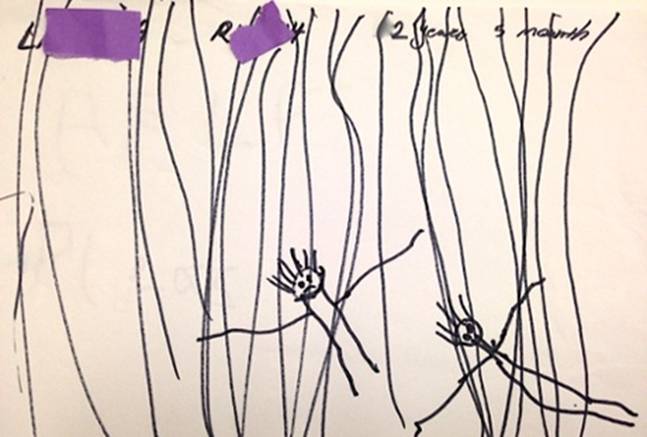

The reality of deterrence is indefinite detention: incarcerated for unlimited time periods with no idea of when you can leave. Every day feels the same: no progress, no change. Just waiting. The reality of deterrence is an illogical processing system that purposefully avoids giving people answers because, judging by statistics, 90% of these people will be approved as refugees. In my time in Nauru I witnessed self-harm, hunger strikes, thirst strikes, psychosis, and the ultimate loss of hope: suicide attempts. Saving lives at sea by ruining lives. Countless times I heard Nauru described by asylum seekers of all ethnicities as hell. If these people could return to their home countries they would.

I wrote The Undesirables: Inside Nauru for many reasons, one of which was to show the Australian people what the reality of offshore detention centres is. If the Australian people are okay with placing people in such conditions in an attempt to shift our responsibilities for protecting the world’s most vulnerable then so be it, but better they make an informed decision than hide behind the falsities and mistruths peddled by both sides of politics and claim ignorance due to this veil of secrecy that has been placed over both Manus Island and Nauru.