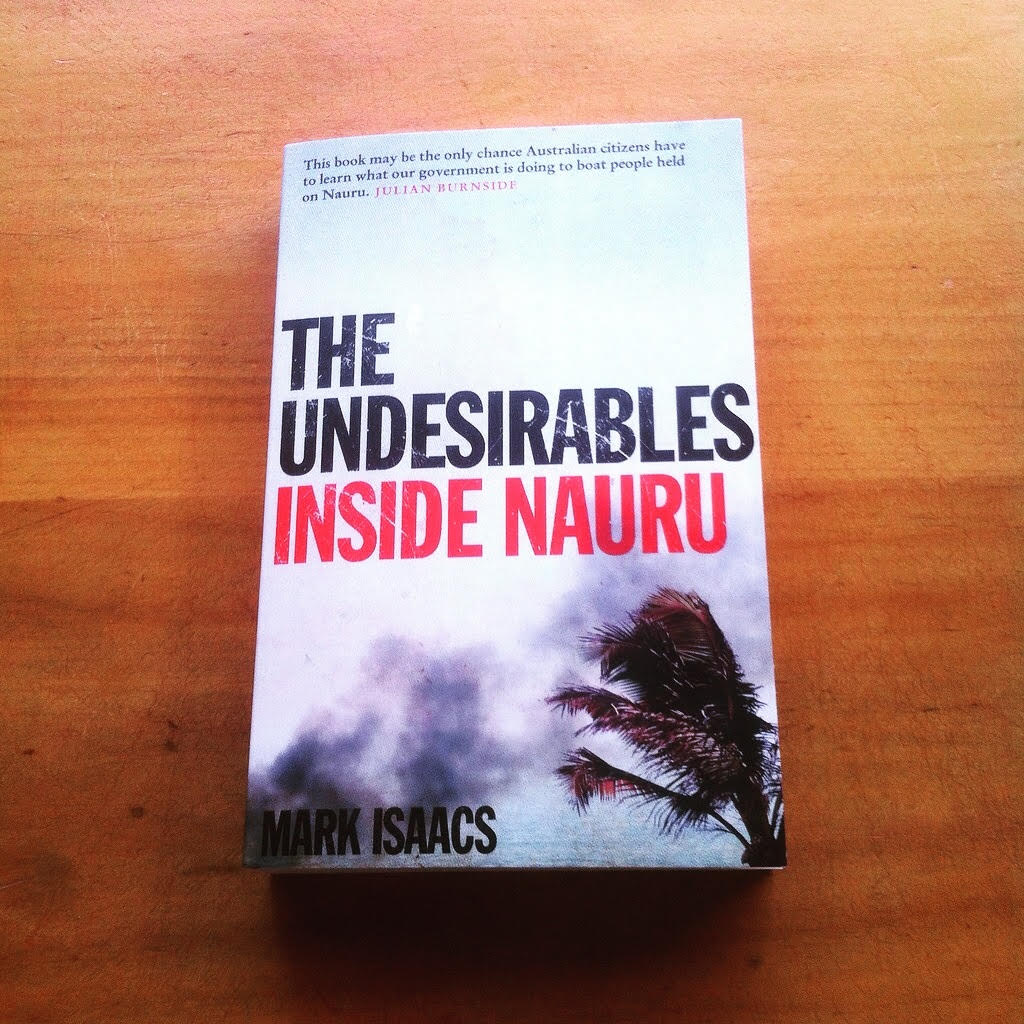

I am very excited to announce that Hardie Grant Books has decided to launch a second edition of my book The Undesirables: Inside Nauru (with a new foreword by Julian Burnside and an updated final chapter by me) in January 2017. This is an excerpt from the new final chapter, first published by Guardian Australia.

Australia is closing the gap between our democratic ideals and the oppressive regimes asylum seekers are fleeing from.

Our greatest fear while working in Nauru – that someone would die while being detained offshore – has been realised many times over. On 17 February 2014 Reza Barati, a 23-year-old Iranian man, was beaten to death by two detention centre staff on Manus Island during a protest. Seven months later, on 5 September, Hamid Kehazaei, 24, who was detained on Manus Island, died after contracting a treatable infection in his foot. Hamid’s death was avoidable, but poor healthcare and bureaucratic delays caused by the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection meant he didn’t receive proper treatment.

Fazel Chegeni, an Iranian Kurd, was found dead on 8 November 2015, after escaping the Christmas Island detention centre. He had been held in immigration detention for four years despite being granted refugee status. A coronial inquest will formally determine Fazel’s cause of death, but reports say he had been psychologically crushed by years of waiting for settlement in the detention system. And then in April 2016, 23-year-old Omid Masoumali set fire to himself while on Nauru in protest against Australia’s treatment of people seeking asylum. He died two days later in a Brisbane hospital, again amid concerns that delays in medical treatment may have prevented his survival.

These are just a few examples of the deaths caused directly or indirectly by the pressures of our immigration system. Since 13 June 2013, 17 people seeking asylum in Australia have died while in detention or in the Australian community. These people have been subjected to horror upon horror upon horror, and yet our politicians continue to justify human rights abuses as humanitarian and essential to protecting our borders. Changes to government and leadership have had no effect on the unofficial bipartisan agreement to abuse people seeking asylum in Australia.

The inexcusable continues to be excused because “We are stopping the boats”. And yet, in the first year the Nauru camp was reopened, the boats had not stopped arriving in Australian territorial waters. When it became clear that offshore detention had failed as a deterrent, the military-led Operation Sovereign Borders commenced in September 2013. Boats suspected of carrying asylum seekers were to be returned to Indonesian territorial waters: a refusal policy rather than a deterrence policy that admits the only way of truly stopping the boats is to forcibly remove people from our waters.

In enacting Operation Sovereign Borders, the government has broken international laws and conventions and threatened our relationship with Indonesia after it was revealed that the Australian navy breached Indonesia’s territorial waters six times. Tony Abbott, prime minister at the time, refused to deny that Australia paid people smugglers to turn around an asylum seeker boat, even while claiming that breaking the people smugglers’ “business model” was vital to “stopping the boats”. The Australian government even donated two patrol boats to the Sri Lankan government to assist it in intercepting asylum seekers fleeing the country by boat.

But even that has failed to completely deter boat arrivals. We don’t know how many boats have arrived in Australian waters since the commencement of Operation Sovereign Borders due to the government’s secrecy surrounding “on-water matters”. However, the occasional story emerges, such as in 2014 when two boats fleeing Sri Lanka were intercepted by Australian authorities. One boatload of people was held on an Australian Customs vessel for four weeks before being deported to Nauru. The other group was returned to the Sri Lankan authorities and the very persecution they claim they were fleeing from. The most recent boat arrival the media reported on, again from Sri Lanka, made it to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands in May 2016.

According to the findings of the Houston panel (the expert panel on which our current detention centre system was designed), stopping the boats was only ever meant to be a “circuit breaker” to allow us the opportunity to recalibrate our regional resettlement policies. However, under the calculating eye of the former immigration minister Scott Morrison and Abbott, the resettlement of UNHCR-registered refugees from Indonesia to Australia ceased as of June 2014. We were removing the “legal” avenues for migration at the same time as we were demanding that refugees adhere to them.

If this was truly about saving lives, the easiest and quickest way to stop the boats would be to bring people to Australia by plane. This would smash the people-smuggling syndicate, it would encourage people to wait for a legal avenue of migration, it would ensure we don’t incarcerate children in torturous conditions indefinitely and it would be a lot cheaper than the billions of dollars spent on maintaining our offshore detention centres.

I’m not suggesting this as an alternative policy. But it is clear: the current system isn’t about saving lives. Our detention centre regime is about taking control of our borders and deciding, as John Howard said, “who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come”.

While there has been little positive change in our politicians’ attitudes towards people seeking asylum in the last few years, I believe there is a growing sense of outrage among the Australian people regarding our offshore detention centre system. The “Let Them Stay” campaign saw thousands of Australians gather in public spaces demanding that the government not return asylum seekers who had been transferred to Australia for medical attention back to Nauru. Doctors at Brisbane’s Lady Cilento children’s hospital refused to release one-year-old baby Asha, who had been badly burned on Nauru, as they feared the government would return her to the island.

All of the state governments, except Western Australia, offered to resettle asylum seekers rather than return them to Nauru. The “Love Makes a Way” campaign has gathered leaders of all religions together in peaceful protest. Our doctors are marching in the streets demanding the closure of Nauru and Manus Island. Whistleblowers continue to defy the Australian Border Force Act. The most famous example was in Eva Orner’s documentary Chasing Asylum. Lawyers continue to battle the legalities of our system in the courts. In April 2016 Papua New Guinea’s supreme court ruled Australia’s detention of asylum seekers on Manus Island to be illegal and ordered the PNG and Australian governments to immediately take steps to end the detention of asylum seekers in PNG.

While the Australian people continue to protest against our politicians’ human rights abuses and fight for a just policy, there is hope that positive change will come. While I agree with the necessity of “stopping the boats”, the answer does not lie in the abuse of children. There are alternatives to the hellholes of Nauru and Manus Island. NGOs, academics and immigration experts have suggested better, more humane ways of offering these people protection through regional resettlement programs and establishing viable migration alternatives. This will mean we have to increase our refugee intake, but we currently accept 168,000 migrants a year; the only reason we can’t find room for more refugees is because our politicians won’t allow it.

There is a glimmer of hope. It seems the Australian government has finally acknowledged that Nauru and Papua New Guinea are unsuitable resettlement options for refugees by offering a “one-off” resettlement deal to the United States for “some” refugees detained in Nauru and Manus Island. At this stage, the details of the deal have not been released, so it’s hard to judge who will be allowed to leave, why they will be prioritised over others, and what is the timeframe of this deal. There are concerns the inauguration of Donald Trump as America’s next president may jeopardise it.

There is, of course, a catch. The Turnbull government is proposing a lifetime ban for those who tried to come to Australia by boat since July 2013, regardless of whether they have been found to be refugees. This accounts for everyone currently on Manus Island and Nauru. Many of these people have family in Australia. Just why they deem this to be necessary is unclear. By their own admission, the boats have stopped and the policy has been a success. What purpose does this cruelty have other than to punish people further?

It is clear we have to find all the people detained in Manus Island and Nauru another home. But by that time they will be traumatised, damaged shells of people, their trust in our country completely eroded.