THE

STORY

What is the caravan?

In October 2018, more than seven thousand people, mainly from Honduras, but also from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, formed what the media called a “migrant caravan”.

The people of the caravan referred to themselves as “The Exodus”. They left behind authoritarian governments, state and police corruption, gang violence, and poverty. Many of them endured violence and persecution in the past and intended to ask for asylum when they reached the United States. Most of the people left family members behind, hoping to find employment in the US so they could send remittances home.

After the first caravan set out, at least three more caravans left Central America on their way north. A humanitarian crisis was looming on the border of the US.

Crossing borders through Central America.

Through the simple act of walking, this exodus of people challenged global concepts of borders, national sovereignty, human rights, and migration. Their march crossed numerous countries, thousands of kilometres, over several weeks, facing numerous dangers and challenges on the road.

They risked their lives for the “American Dream” but at the end of their journey through Central America nobody knew how they would be received by the US government.

Entering America

The migrant caravan provided safety in numbers for its members on the dangerous road north to the United States. Now that the caravan has arrived in Tijuana on the Mexico-US border many people in the caravan intend to ask the US government for asylum. Many have already asked for asylum in Mexico and have been awarded refugee visas. Some are trying to seek third-country resettlement through the UNHCR office in Mexico. While others will no doubt attempt to jump the border wall or cooperate with smugglers to enter the US.

THE

JOURNEY

How I got into this?

I was living in Mexico City when I heard that the migrant caravan had crossed the border from Guatemala into Mexico. After following the news of the caravan’s passage through Mexico for a week, I flew to Tuxtla Gutierrez – the capital of Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state – and hired a car. I wanted to see this phenomenon of human desperation for myself.

I was only meant to follow the caravan for a few days. However, I quickly became intrigued by the unique story of the caravan and the people involved.

The podcast

This is the full story of the migrant caravan, how it was formed and how it travelled north to the US border, told by members of the Exodus themselves.

How the caravan works

How did so many people remain united across such a large distance in the face of numerous risks and challenges? The reality is the caravan would never have made it to the US border without internal management and external guidance from a pre-existing external network of Mexican civil society groups. But ultimately all decisions were ultimately made by the people. The result was organised chaos.

The Peace March

On Sunday 25 November 2018, members of the Exodus organised a peaceful march to the US-Mexico Border to protest against the slow processing of asylum claims by the US government. The men, women and children were stopped a long way from the border by a heavy Mexican police presence. When members of the march evaded the police blockades, the action got out of hand.

The Wall

The wall is an ugly, distinctly unnatural structure. A monument to prejudice, isolationism, fear and hatred. Many people in the caravan see the wall as another obstacle to overcome and are willing to cooperate with people smugglers to make the jump.

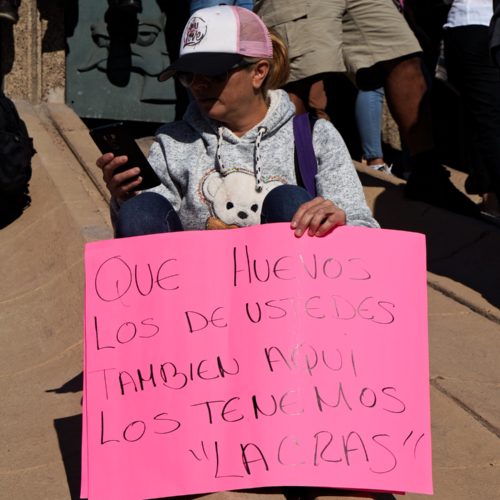

Anti-migrant rally

A small but vocal group of protesters in Tijuana march to the shelter to voice their opposition to the migrant caravan. While their views are xenophobic, racist and ignorant, I hear similar opinions throughout my time in Tijuana. Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that some people feel aggrieved by the support of the migrant caravan when so many Mexicans are poor.

Tijuana

When the caravan arrives in Tijuana, the physical march to the US is more or less over. However, the most difficult part is yet to come. The US government is only accepting 40 asylum applications per day. With thousands of names on the list, the wait in Tijuana will be extended. But how will the people of Tijuana feel about this disruption?

From Mexicali to Tijuana

The Rumorosa highway from Mexicali winds it way through the Sierra de Juárez Mountains of Baja California. Loose rock outcrops build towards the sky. A wide, scrubby desert stretches to the US border and beyond, fading into the hazy horizon. On the other side of the mountains the road beelines for Tijuana and the west coast.

Mexicali

Mexicali is a dusty border town. The people of the caravan are packed into the few available guesthouses. Those who can’t fit sleep outside on the street in the middle of the red light district amongst prostitutes and drunks. There is only one road left to Tijuana and their hopes of entering the United States.

Jalisco, Sinaloa and Sonora

Travelling through the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Sinaloa and Sonora the Exodus faces numerous challenges. With more than 2,000 kilometres of road to cover, parts of which are infamous for drug cartel operations, the caravan is dislocated and separated by unreliable assistance from Mexican state governments.

CDMX to Queretaro

The people of the Exodus begin walking to the highway. Their path takes us alongside busy roads and underneath overpasses. Blaring horns fill our ears. Pollution and smog is blown in our faces. But after weeks of walking the people of the Exodus are accustomed to this life. People on the road become people of the road.

The Assembly

Public assemblies are held every evening to decide the Exodus’ next steps: whether they will move, what route they will take and what time they will depart. Any migrant can stand up and speak at the assemblies. This assembly in Mexico City is a significant one: which route should they take north to the US border?

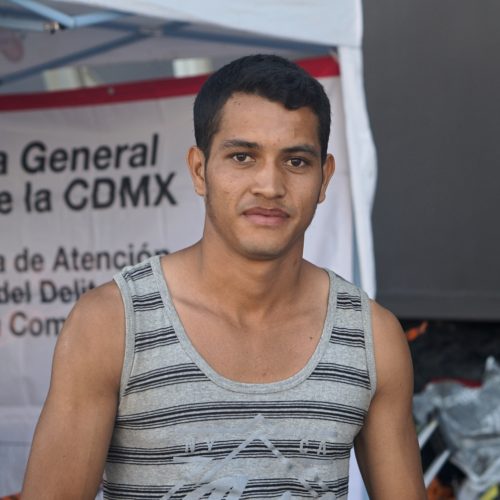

The stop at CDMX

The Exodus has arrived in Mexico City and is being hosted in a sporting complex at the Magdalena Mixhuca Sports City. The reception in Mexico City feels like a carnival. Everywhere I look there are tents for NGOs and church groups offering all sorts of services. It is expected that the people of the caravan will make the most of the city’s hospitality and stay for a few days.

From Chiapas to Oaxaca

The caravan leaves the land of the jaguar behind on its way north to the land of the coyote. It passes through the reddish-brown corn fields of Oaxaca, little haciendas and rancheros, and jimadores cutting agave plants. It’s a picturesque setting for a mass migration.

Finding the caravan

After following the news of the caravan’s passage through Mexico for a week, I flew to Tuxtla Gutierrez, capital of Chiapas; Mexico’s southernmost – and poorest – state, and hired a car. I wanted to see this phenomenon of human desperation for myself.

THE

PEOPLE

Who are they?

The people of the Exodus are mothers, brothers, children and grandparents. Each of them have left homes and families behind in their search for the American dream. These are their stories of why they left and the journeys that brought them to Mexico.

Dulce Celeste

Persecuted Trans Woman from Guatemala

She is from a village called El Petén in Guatemala, located about 8 hours from Guatemala City. She describes her village as being “the arse of the devil”. She lived with her sister before she joined the caravan.

She was 15 years old when her mother died. After that she gave herself to liquor and “walked away from life”.

She worked for a fishing company called Paradise Springs but the company closed and they fired all the staff. She was out of work for 3 months and then she heard news of the caravan and she decided to leave. She was terrified of the journey, but she somehow found the courage and left.

“I did not bring anything. I threw everything away. What I would have liked is my dresses and all of my paintings.”

She jumped in the back of a trailer, leaving her house in El Petén at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. That night she slept on the floor of a stranger’s house and the next day she found the people of the caravan.

Lack of work wasn’t the only reason she left. Like many people in her situation, lack of work simply precipitated her departure.

“I saw that they killed people in my town and I was scared. And so I came,” she tells me.

She tells me she had a husband of 9 years and then last year they separated. He found another woman, and they had children together. Dulce spent the next 6 months drinking, crying and yearning for him. Her partner lived next door to her sister. When they split, Dulce built a little wooden house for herself away from them so she wouldn’t have to see him. Because if she passed his house, she couldn’t stop crying.

Dulce tells me there is a lot of discrimination in Guatemala against trans people. Her husband’s parents did not like their relationship. One day the police arrived at her house and told her that her husband’s dad had paid 3,000 quetzales (almost US$400) to kill her. She believes her father-in-law convinced her husband to leave her because he wanted a grandchild. Dulce and her ex-husband are no longer in contact.

Even now, in the caravan, Dulce is concerned for her safety.

“It is very dangerous,” she says. “Children have been lost.”

Thus far she has only endured discrimination, but as a trans woman she doesn’t feel safe walking alone at night in the caravan.

“It’s the same on the street as in the caravan,” she says.

She says there is about 60 or 70 people in the caravan’s LGBTQI community. They travel in a group for safety.

“We have come to know each other here. We are all united.”

Dulce’s American dream is to work for about 5 years and earn enough to build her a house, establish a business, and help her family. After that she will return to Guatemala.

“And look for love, too?” I ask.

“Yes. Yes. Because one nail drives out another, as they say,” she replies.

It may be hard for some people to believe they have something in common with a persecuted, impoverished trans woman from Guatemala, but her story is essentially one of a broken heart and a dream for a better life.

Neri Martinez

Is covered with the blood of Christ

are members of the caravan who volunteer to help guide people to each destination, arrange

rides on trucks, and ensure nobody is left behind.

Neri Martínez is one of these volunteers.

“Here we are all equal. Here the only leader is God,” he says. “If there was a leader, Juan

Orlando, the president of Honduras, would have that person captured because they would have

enormous political influence.”

According to Neri, the caravan started because of the injustices and corruption of the Honduran government.

“The United States sends aid to Honduras, but the governors eat it. The poor do not look at the money.”

News of the caravan was published on social media and people saw an opportunity to escape. Neri thought about leaving his country for 10 minutes before he decided.

“I leave covered with the blood of Christ. The Holy Spirit accompanies us, and if God is with us, who is against us? If Trump opposes God, God is able to take it away tomorrow, if He wants to.”

According to Neri, the intention of the caravan is to sit down at the border and claim the right of the migrant.

“We have the right to a better life.”

Herman

Father travelling with 17yo daughter

Herman is worried about the mines that are exploiting the land.

“Supposedly Honduras will end up like a desert,” he says.

It is widely reported that mining in Honduras is linked to water contamination, deforestation and environmental degradation, human right violations, as well as conflict and violence due to land grabbing.

Herman is worried that the Honduran government wants to privatise health and education. He believes the president, Juan Orlando Hernández, is becoming dictatorial, controlling all the powers of the state and supported by the armed forces.

“He was re-elected without consulting the people,” Herman says.

The dubiously run 2017 election was called a “low-quality” election by the Organization of American States, which called for fresh elections hours after President Juan Orlando Hernández was declared the winner. The Hernandez government suppressed the subsequent protests which resulted in at least 17 deaths.

“Honduras is like a war,” Herman says. “Inequality is awful and the families fight with each other. Some of them are in the government, earning a better life and earning a salary. But most of us are just being jerked off.”

Herman heard about the caravan from a televised news segment. When Herman heard that the caravan was leaving he told his 17-year-old daughter, “Let’s go.” They took some money and left his wife and 4 other children at home. His youngest child is 2 years old.

“Nobody likes to leave their family alone and without food,” Herman says.

Herman has tried to reach the US ten times but each time he attempted he was caught by Mexican authorities. He can’t afford a coyote so he takes the cheapest and most dangerous route north: hitching a ride on “The Beast” freight train. The last time he tried to cross was two years ago.

He has family in the US but he doesn’t expect them to help him.

“What I think is that God will allow me to enter the United States to work, but on my own. There is no support, only God.”

His faith in God also allays his concerns for his daughter’s safety.

“If something happens to her, it has to happen to me too. All or nothing. Only God.”

The caravan was not organised by any one person or one group. According to Herman, the people of Central America are going through a crisis of leadership. They their countries en masse, an exodus of people.

They left by the mountains because the Honduran government would not let them leave.

“They want to privatise our freedom to go to another country,” Herman said.

They followed the road to Ciudad Hidalgo on the Guatemalan side of the Mexico-Guatemala border. When they reached the border blockade, Herman and his daughter spent 3 days on the bridge not believing they could enter Mexico. People told him to go.

“Let’s move!” they shouted.

In the end he saw that there was no other way, so he and his daughter crossed the river on two big tires. When he arrived in Hidalgo City he saw there were thousands of people in the caravan.

Herman believes the Mexicans have been so kind to the Hondurans because they know what it’s like to be poor and have not become “money-sick”.

“For God there are no borders. For God everything is freedom but in this world the earthly laws are dominating. If the kingdom of God was for the millionaires, we the poor would already be in hell. But the Bible says that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man enter the kingdom of heaven.”

Herman believes that Donald Trump is ready to shoot the migrants but Herman is willing to approach border knowing this.

“Donald Trump is a super millionaire who has no compassion or pity for us poor people. We are not a gang of thugs. We are looking for a new future for our family who are suffering in our country. I am a man of work, but I can not carry out my work in Honduras. Let us arrive together so that we can talk to Donald Trump’s heart and if he has a heart of stone, let God use his little finger and it will soften.”

Andrea and Maria

Single mothers travelling with their children

She is a single mum, aged 27, travelling alone with three children, aged 2, 7, and 11. This is her fourth attempt to go to the US.

When Maria was 9 months old, her mother moved to the US and gave Maria to her sister. Maria was raised by her aunt until she was 15 when her biological mother asked her to live with her in the United States. She didn’t explain to me how she arranged her travel to the US, but Maria and her brother lived in Houston for a while until they were deported.

She returned to Honduras where she started a family. Since then she has tried to go to the United States three times, each time without her children. On one occasion she rode the dangerous freight train, La Bestia. In the third attempt she was kidnapped by a cartel for two months. During this time, she did not see the light and she never knew if it was day or night. The ransom was set for US$5,000 and one day before her family paid, she was rescued by the Mexican authorities. When she returned to Honduras she was so thin that her friends did not recognize her.

During this time the father of Maria’s children took care of the children in his house in Honduras, but he neglected his responsibilities. The children did not eat and he started heavily using drugs. He sold all Maria’s property and he slept with her cousin. When Maria returned there was only one bed left in the entire house.

Since January of this year she has been trying to find a job to take care of her children.

“Don’t call us, we’ll call you,” prospective employers told her.

She has not had a job all year. Instead, she sat on the sidewalk of her house and begged for food for her children. Her mother who lives in the US sends her US$50 dollars each week to support her.

Maria’s mother is lonely and wants Maria and the children to live with her in the United States. She sent Maria money to travel by bus and find the caravan in Guatemala. However, Maria is afraid to continue on the trip. She’s afraid for her children.

“If my mother wanted me more, she would send money to pay a coyote,” Maria says, with a frown.

Andrea walks and travels by bus with her 4-year-old child. She is divorced from her husband but they live together. When she heard about the caravan she joined, leaving her two-year-old child with her ex-husband, the child’s father. Now Andrea’s ex-husband is thinking of joining the caravan but he is waiting to see how the journey pans out.

Andrea says that yesterday a family she knows paid a coyote who picked them up in Mexico City. Andrea and her ex-husband are waiting to see if they should pay a coyote or continue with the caravan. I later see her in Queretaro with her young boy. She has elected to stay with the caravan for now.

Andrea and Maria tell me that the two men who are sitting next to us took a bus to Monterrey to continue the trip with 4 more friends but when they arrived, operatives from a drug cartel chased them and caught their 4 friends. The two men who survived and made it back to Mexico City are “dead scared” and are going to return to Honduras.

Vincent

The mother of his children killed his aunt

“I’m a man who has suffered since I was a kid. When I was 2 years old, a man raped my mother, then he killed her and threw her body in a river.”

Not long after his mother died, his grandmother died of cancer and his father became a deeply depressed alcoholic. Vincent was raised by his grandfather, and occasionally his father’s sister.

“I was 17 when I fell in love,” Vincent says.

He married a young woman from his neighbourhood and his grandpa gave them a little land on which he built a champita, a small wooden house. He called his first daughter, Andrea, which explained the tattoo on his forearm.

“After her, Juan was born, and then a third child. This is how it happens in poverty. You get a lot of children very quickly.”

At this point, Vincent’s dead mother’s family returned to his life. They questioned him about his future, his plans and his poverty. They suggested he move to the USA and join up with their family members in New York.

“We cannot go alone to the border,” Vincent tells me. “You have to pay a coyote [a people smuggler]. It is a mafia, but it is the best way to avoid getting kidnapped by the cartels. When that happens they treat you very bad. If your family doesn’t give them money, they can kill you.”

”

I couldn’t believe that the mother of my children could kill my aunt

Vincent tells me that to enter the US with a coyote costs US$4,000. In 2012, his mother’s family helped arrange his illegal travel through Mexico and into USA.

He found it difficult to settle in America. He found it a closed society, at times racist, and he couldn’t learn English, although he tried. He missed his family, especially his baby who had only been just born.

“I wasn’t used to being alone. I used to cry every night.”

He found work in construction and was able to send money home to his family. But after eighteen months, his wife fell in love with another man and stopped caring for their children. She started taking drugs and associating with unsavoury folk, and she became an addict. When Vincent found about the affair, he arranged for his aunt in Honduras to take care of the children while he continued to send money home. When his wife stopped receiving money she became jealous and spiteful. One day, she tried to take the children from Vincent’s aunt, but his aunt sent her away.

“She went back to my aunt’s house that night with two men. They shot and killed my aunt. Someone contacted me to tell me what had happened. I couldn’t believe it, I fell into a depression. I couldn’t believe that the mother of my children could kill my aunt. She threatened my family and myself. My plans were shattered.”

In 2016, after almost five years in the United States, Vincent returned home to see his grandpa before he died. The mother of his children had been sentenced to 20 years prison, but his children were with the family of his ex-wife.

“The family didn’t tell the children what had happened, but at some point they will learn the truth.”

In his hometown of Santa Cruz de Yojoa, there are mountains and waterfalls, rivers and lakes. But there were no jobs and there was a lot of violence. Like his father before him, Vincent became depressed. He sold the house he was building, started drinking, and spent all of his money.

He tried to re-enter the United States in 2017, with neither a caravan nor a coyote. When he arrived at the town of Reynosa, Mexico, he was caught by immigration without papers and he returned to Honduras.

On another attempt, he managed to enter the US at Reynosa with the help of a coyote. He jumped the border wall and crossed the Rio Grande in a little inflatable boat. The coyote hid the group of 54 people in a warehouse for five days, but immigration officers found them and arrested them all. Vincent was detained for 3 weeks and then deported back to Honduras.

He moved to San Pedro Sula, which for a time was considered one of the most violent cities in the world, where he met Eva and they had Madeline. But Vincent was aware that their lives were in danger.

“My ex-wife has threatened to kill me. She has said that she is going to send people to do so. That is why I decided to come here.”

The challenge for Vincent is the cost of coyotes. A special trip designed for those with children costs around US$7-10,000. That’s why Vincent thinks the caravan is a good opportunity to reach the US safely.

“The caravan is protected. If we arrive together, we are safe. We want to ask the American government to take us as refugees. We want a dialogue.”

Even though it is their legal right to seek asylum in the United States, it is unclear whether that will even be possible. President Trump has indicated the troops being sent to the border will block the migrants from requesting protection.

The most tragic part of Vincent’s story is that it is not unique. This migrant caravan is full of stories just like his.

Eva and Madeline

A mother and her 1-year-old

Eva is married to Vincent (32). They are travelling light. They don’t even have bottles of water or food. The other day a pregnant woman and her unborn child died from sickness and heat. This has Vincent and Eva worried for Madeline who has been vomiting from a stomach bug.

The family left Honduras when Vincent's ex-wife threatened their lives. Vincent's ex-wife is currently in jail for murdering Vincent's auntie. This is the second time they have tried to immigrate to the US before, but they hope they will have more luck with the caravan.

Mari and Javier

A single mother and her child with down syndrome

Mari and her children lived in San Pedro Sula where their family was terrorised by gangs. Mari had to pay a tax, like rent she says, to the gangs in the area. When she couldn’t pay, gang members burned down her house and murdered her two brothers. She has scars on her hands which she says were caused by the gangs.

She left Honduras to make a better life for her other children. She brought Javier with her on the journey and left the other two behind with family. She hopes to bring them to the US when she has more money.

Travelling with Javier has been very difficult but it has its benefits. People offer food and items for her and Javier because he is “special” she says. However, Javier is also a target for discrimination. People physically and verbally abuse him. They push him out of the lines for food. This happened in Honduras too.

Javier was born with hydrocephalus, a condition where excess fluid collects in the brain. He easily gets dizzy and complains of headaches. He suffers regular seizures, but Mari can’t afford his anticonvulsant medication. Doctors have told María that he needs surgery, but she’s never had the money.

Mari and Javier want to apply for asylum in the US.

Marta

A US citizen living on the Mexican streets

“I’m homeless but nobody gives me anything,” she growls.

It’d be easy to ignore her but I stop and explain to her that I’ve been following the caravan for several weeks and have come to learn these people’s stories.

“Helping them, shouldn’t stop people helping you too,” I say.

Her attitude softens and she starts to tell me her story.

She’s an American citizen who fled the US after committing a crime. Her family tell people she’s dead because they are too ashamed to admit that she lives on the street in Zona Norte, Tijuana.

“I shouldn’t think about what they get, I should be thinking about my situation and what I need to do to improve myself,” she says. “Yesterday one of the migrants gave me 20 pesos. I almost cried.”

Even now she chokes up with emotion.

“I judged them too early. They’re scared, I can see that. They’re a long way from home, everyone hates them. I know they feel.”

Martha poses for a photo with her dog and her friend. I’m glad I stopped to talk to Martha.

Marcelo

A member of the LGBTQI community

A human rights organisation arranged and paid for separate transport from Mexico City all the way to Tijuana for the LGBTQI community. Marcelo tells me he did not know about the buses.

“Most were not told. They just kept it for themselves, and they left.”

Marcelo says he has a good relationship with his family. He has four siblings, aged 24, 22, 15 and 6. Marcelo didn’t work or study in Honduras. He spent most of his time in his house while his parents work. He says there is discrimination and violence against homosexuals in Honduras and he mentions that he was raped as a child. His family are happy that he is trying to reach the US but they are also afraid for him.

Jenni

A 19-year-old construction worker

Jenni believes her father is a well-respected figure in the community because of his generous work as a pastor.

“All the people love him.”

When Jenni graduated from high school, she began working as a cleaner in a house in Guatemala City, 4 hours from her family home in Morales. She didn’t like working in the house, cooking and cleaning, She preferred to get up at 6 in the morning and go with her dad to work as a mason. She liked the fact that people were surprised to see a working girl with sweat on her brow. She helped her father build their local church.

Jenni tells me Guatemala is dangerous. Where she lived in Morales there are many gangs. There is a plaza called "La Línea" where men spend their time drinking. A lot these men are armed with guns, she tells me. They intimidate women and she says girls have been taken in cars and raped and killed.

According to Amnesty International, thousands of people continue to flee Guatemala to escape high levels of inequality, violence, impunity and corruption. Human Rights Watch reports that violence and extortion by powerful criminal organizations remain serious problems in Guatemala.

”Gang-related violence is an important factor prompting people, including unaccompanied youth, to leave the country.”

Christian called Jenni the evening before he was leaving for the caravan to ask her if she wanted to come. She had less than 24 hours to decide if she would join him. Jenni’s father didn’t want her to travel in the caravan because he believed it would be too dangerous, but she left anyway.

Jenni wants to live in the United States so she can work and help her parents. She doesn’t speak English, and she is unsure how she will learn if she has no money. She has an aunt who lives in the US who will help her settle.

Christian

A gun-slinger from Guatemala

When I ask Christian why he left Guatemala he tells me he is crime-free. He left Guatemala for an adventure. “To explore,” he says. When I remark that this is a dangerous way to adventure, he replies, “I like danger” and laughs. He say he likes guns, which makes me think he’ll settle just fine in America. His uncle gifted him his first gun when he was 15. When he was 17, he bought a 9mm. He once shot a man in the leg, although he says it was in self-defence. He says gun violence is normal in Guatemala and that he is used to fighting in the street. He is full of young male bravado. In the context of Guatemala this adds an element of violence and danger. Although his family are evangelists, Christian is not a believer.

Christian was in his hammock when a friend of his told him about the caravan and encouraged him to join. Christian and his sister Jenni joined a group with coordinator in Morales. It took them two days to join the caravan.

“This is a good opportunity to not get killed. It is a unique experience,” Christian says.

It was easy to find the caravan in Guatemala. The problem was when the caravan arrived in Mexico. They were stopped at the border by Mexican police. It took them four days to cross the border, but they eventually crossed in tires on the river.

Christian left behind his pregnant girlfriend in Guatemala. When he arrives in the US, he hopes to send money back to support her and his child.

David

The supermarket worker

He studied until junior high school and then worked in a supermarket for two and a half years, sweeping the floors, throwing out garbage and working as a cashier. The salary was extremely low, but he wanted to occupy his time in something good like a job. He didn’t enjoy the work but he was thankful for it because it taught him what it meant to work hard.

David tells me work in Honduras is not secure.

“You do not know if you have work today and tomorrow you do not.”

He believes that his employers exploited their workers who had no rights or benefits to their employment.

David worked this year and last without a signed contract. In October he received news that his employers were firing the majority of staff.

“Since I was new at work I was going to be one of the first to leave.”

In the fortnight before his final day of work, he heard about the caravan for the first time.

It was payday and he was standing in line at the bank. He heard everyone in the line saying that the caravan had left for the Guatemalan border at 6 o'clock that the morning from San Pedro Sula. He always had the intention of going to the United States but he did not want to go with a coyote. When he heard that three thousand people had joined the caravan and were walking to Guatemala he was inspired. His co-workers told him there would never be a safer, easier opportunity to arrive than with the caravan.

The next day David told his brothers and his parents about his intention to join the caravan. His parents were not happy with his decision but his brothers offered their support and eventually his mother relented and informed their relatives in the US that David was on his way.

“They all have been praying for me,” David says.

David took a bus at 4am, arriving at the Honduras-Guatemala border at 7pm. There were already 300 people there waiting for the caravan. The border authorities said they wouldn’t let anyone pass but when the caravan arrived at noon the next day and the authorities saw the multitude of people they relented.

David said that the journey through Guatemala was calm. They walked in small groups, occasionally receiving support from trucks. He believes others who arrived after the caravan avoided the border authorities by travelling through the mountains.

David knew little about the customs of Guatemala, but the people of the caravan supported one another.

“The caravan is a valuable support for many. We provide each other safety and courage along the way.”

They had their first real difficulty at the Guatemala-Mexico border where they were denied entry into Mexico by Mexican border authorities and police.

“It was a complete mess and a lot of desperate people wanted to break in. The federal police opposed them in a violent way. After a while everything calmed down.”

While the majority of people waited at the border, some members of the caravan began crossing the river to enter Mexico. When people realised that it was possible to cross the border like this, they all began to do it.

When they arrived in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, Mexican civil society groups were expecting them with food and supplies.

David says the walk from Ciudad Hidalgo to Tapachula was the most complicated leg of the journey. They left at 4am and walked for twelve hours without a ride until they arrived in Tapachula. One of David’s friends was walking next to him and fainted mid-conversation. David blew some air on his face and his friend started breathing again.

In Tapachula, most of the people in the caravan were scared that they would get sent back to their countries. They believed that those who moved independent of the caravan would get caught and be deported. They also said that it was dangerous to be moving alone by night.

That evening a massive storm hit and made a lot of the walkers sick with flu. A lot of people considered leaving. The ones that could paid for hotels. The next day the caravan left for Huixtla. Some people paid for buses but they were scared that they might get caught by immigration officers. Some buses refused to provide service to avoid problems with Mexican officials.

“No one really knew what would happen. We were told that there was going to be some support or rides but in the end there was nothing.”

David paid for a bus and once on the bus he could see the desperation of the people looking to get a ride while their children suffered under the hot sun. Some people waited until noon to catch a ride.

When David arrived in Huixtla, he joined a group of eight who gathered their money and paid for a cheap room in a hotel. Most of the people slept on the floor since there was not much space. Most of the people from the caravan arrived at the night. People slept in parks, on the streets, in malls or parking lots.

Despite the hardships, David tells me the trip has been a marvelous experience. He has enjoyed seeing landscapes that he previously only ever knew from the internet or television.

“I’m thankful to God since I’m in good health, but I see how complicated the situation is for some of my friends. They have struggled with their health. Thank God they are better now with the support of the Mexicans who have helped us with medical aid, food, and water.”

His American dream is to find work and help his family. Little by little he will ask “our Lord” for a better job opportunity; for a future; for him and his family.

Juan and Lily

A father and his daughter with cerebral palsy

Erik

A family is chased out of El Salvador by gangs

“My country is in chaos at the moment. It’s ruled by gangs. The Maras.”

When Erik talks about the gangs he could be referring to the Mara Salvatrucha, also known as MS-13, El Salvador’s most notorious gang. But he could just as easily be speaking about El Salvador’s other two major gangs: the 18-Sureños and the 18-Revolucionarios.

In 2016, the NY Times reported that gangs in El Salvador had “an estimated 60,000 members in a country of 6.5 million people” and they maintained “a menacing presence in 247 of 262 municipalities.”

Erik tells me he was extorted by gangs in San Salvador. Each week he had to pay US$20 or he risked physical repercussions. According to the NY Times, gangs extort about 70 percent of businesses in the country.

Erik was worried about the threats to his daughters.

“Once girls come of age, 12, 13 years, the gangs already want to take them away and make them their women.”

Erik’s eldest son was 21 years old when he was murdered by gang members.

“They treated him worse than an animal,” Erik says. “Today, being young in El Salvador is a crime. Young people are being killed in El Salvador every day.”

His youngest son was 17 years old when gangs started trying to recruit him. Erik refused to have his son join them. In retaliation, gang members broke into Erik’s house and pistol whipped Erik, slicing his head open. They gave him 24 hours to leave his house before they would come back. Erik and his family left their home and all their belongings behind and fled the country.

Erik and his family joined the second caravan from Central America in Tapachula, Mexico. He heard about the caravan through a Facebook page run by an organisation called Pueblo Sin Fronteras [People Without Borders] which provides updates on the caravan’s movements through Central America. The involvement of Pueblo Sin Fronteras convinced him to make the long journey to the US.

“They guide you through the way. I wouldn’t have known where to go. I would’ve taken any road,” he says.

Eril is thankful for the help of the volunteers at Pueblo Sin Fronteras who have been travelling with the caravan ensuring nobody is left behind or is caught by immigration.

Erik is travelling with his entire family: his wife, his father, his two children (a daughter and a son who is now 18), and his son’s pregnant girlfriend. He has no family left in El Salvador and he has no home to return to after the gangs kicked them out of their house.

Thus far, Erik and his family have been travelling for a month. They left their country with no money so they can’t pay for transport. The longest they walked in one day was about 36 kilometres.

“We walk and we hitchhike, under the sun and the rain, with hunger and thirst. I am diabetic. My feet fall asleep. I get dizzy. But I want something different for my children so I sacrifice. Thank God Guatemala and Mexico have been good to us.”

In Mexico, the authorities have provided food, water, and medicine for his diabetes.

The second caravan is also aiming for Tijuana. And there is a third caravan of approximately 3,000 people from El Salvador following them.

Erik doesn’t know much about the route but the people of the caravan say it’s dangerous. He has heard that between Guadalajara and Tijuana people get kidnapped. He places his and his family’s fate in God’s hands.

“If God allows it, we will cross. It is Him who has the last word. He is sovereign and he knows each family’s needs.”

Erik has family in Australia who fled El Salvador during the civil war in the 1980s. He thinks they found asylum in Australia through a UNHCR resettlement program.

The civil war in El Salvador lasted 12 years from 1980-1992. It was fought between the military-led government which took power in 1979 through a coup and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front. The military government was considered an ally of the United States and was financially supported by the Carter and Reagan administrations, despite its poor human rights records which included targeting civilians with death squads and recruiting child soldiers.

Erik remembers the military assassinating people in cold blood.

“They dropped bombs on the hills and a lot of innocent people would die. The war was hard.”

His family did not fight in the war. They are Evangelical Christians.

“Since we were young my father set the fundamentals that God exists. He’s the king of kings. He is the life-giver. God comes first. He has to be number one in our lives.”

Erik’s family contemplated applying for asylum to Australia, but his dad was worried about moving because Erik and his sister were very young. Erik can’t imagine how different his life would be if they had followed their family members to Australia. Thirty years later, Erik is determined to save his family.

This is the first time Erik has tried to reach the United States. He has no family in the US but his wife’s mother lives there. I find it strange but so far they haven’t talked to his mother-in-law about their trip. Erik says that he and his family intend to ask for asylum.

“We are chasing the American dream, as everyone says.”

This will be made more difficult by the Trump administration’s attempts to restrict protection for people fleeing gang violence. Perhaps Trump should consider the history of US involvement in El Salvador and the role previous US governments have played in the deteriorating situation of the country before making decisions that could endanger the lives of people like Erik and his family.

While we speak Erik’s son arrives. I didn’t realise this but Erik had been sitting at the entrance to the stadium waiting for him. They had got separated when his son left on another bus and Erik didn’t know what had happened to him.

“Don’t be doing that,” Erik chides his son in front of me. “We were worried.”

Erik hugs his son and smiles at me. He looks tired.

John

An American citizen sees himself in the caravan

When John heard that I was visiting the migrant caravan in Mexico City, he asked me if he could join. His whole life he grew up hearing stories about people migrating from El Salvador to the US. Now he had the chance to witness this process firsthand.

“Had circumstances been different my family could’ve stayed in El Salvador and that could very well be me trying to come to the US for an opportunity. It’s wild how these small decisions drastically changed my life,” John says.

John’s maternal grandfather worked as a farmer on other people’s land until he saved enough money to buy his own plot. John’s grandparents and their 10 children lived in a tin shack which used newspapers as insolation for the walls. The biggest building in their town was a train station. They didn’t have electricity in their home and they were better off than John’s dad’s family.

John’s family decided to come to the US on a whim. His aunt was already living in the Washington DC area and she told John’s mum about the opportunities. His mum flew into the US after arranging a visa and stayed there. His dad was working on merchant ships and border security wasn’t as tight as it is now. His ship stopped in Baltimore and when he stepped off the merchant ship he never returned to the boat. John’s older sister, who was born in El Salvador, was left behind with John’s grandmother. His parents wanted to see what the US was like before relocating her. They didn’t want to put her through the hardships of the move. They came to the US with just the clothes on their back.

Once they had established themselves, John’s mum sent money to his grandmother to finance his sister’s journey. One of the friends of the neighbourhood was travelling to the US by land and John’s sister went with them. His sister was only 6 years old but she still vividly remembers the trip. She walked and took trucks all the way to the Mexico-US border. They crossed the border in a dump truck. The people crouched down and the smugglers put wooden boards over them and threw dirt on top of the boards to hide them from view. It was difficult for her to breath and she was afraid of being caught. Nowadays she’s a US citizen, she’s educated, and she has a good job. But she still thinks about that trip.

John’s parents didn’t become citizens until the late ‘80s during the amnesty period of the Reagan administration. But John’s family isn’t grateful to Reagan. The Reagan administration supported and financed the military-led government during the El Salvador civil war which decimated the country and killed thousands of civilians.

The rest of John’s family slowly migrated to the US. The family would save money, send it home, and bring another family member over. John’s grandmother had 10 children: 5 girls, 5 boys. The first 6 of her children entered the US illegally. His aunt, who was the first person from his family to arrive in the US, petitioned for the other 4 children to come to the States. It took years but eventually they were given residency. John’s uncles arrived as teenagers and went to high school in the US. John’s whole family lived together in an apartment for a long time before they built the financial base for themselves to move out.

Nowadays, his dad drives commercial garbage trucks. For a long time he was a long haul truck driver. It was good money but the work hours were hard on the family. He would leave on Sunday and come back on Friday. During the summer vacations John would join his dad in the truck for a week. These were pre-cell phone days so all they did was talk.

“He was seven when his dad left. His family were so poor that on the rare occasion his mum drank a Coca Cola, he used to swill her backwash just so he could get the flavour. To him it was a delicious treat.”

When John’s mum first moved to the US she cleaned houses for a living. When she became a citizen and had learned English she started working as a custodian at a museum in Washington DC. That makes her officially a US government employee. She’s been working there for 20 years.

John’s parents achieved the classic American dream. From undocumented migrants to buying their first home together. Their children went to college and now they live in a safe neighbourhood.

“It’s surreal hearing the stories of my family, seeing where we have come from to where we are. It’s humbling. A lot of people don’t appreciate just how much effort and perseverance and hope it took them to get to where they are today.”

His dad would love to go back to El Salvador. In his dad’s mind, El Salvador is still his home. He still owns a house and has siblings in El Salvador. He has nostalgia for the El Salvador he grew up in. John’s mum doesn’t feel the same way. Her whole family live in the US. John doesn’t foresee them ever going back, especially with the gang violence in El Salvador.

John spent the next few days visiting the caravan with me, speaking to people. Considering his background it is no surprise he is empathetic to their stories.

“I completely understand why you would risk your life to come to the United States. It makes perfect sense. If your back is against the wall, you have no economic opportunities, gang violence is knocking at your door, what do you do? You take the only out that you have even if the risk of something happening is high. You drastically change not just your life, but the life of the people you leave behind. Your brothers, sisters, kids, mothers, fathers, whose lives are drastically going to improve as well by this person taking the risk.”

John was surprised but encouraged by the positive, hopeful atmosphere in the caravan. The stories he heard of his family’s experiences were much darker. He thought the people would be more terrified. But he believes they see power in their numbers. He thinks this makes it easier for the families and children. But he is not optimistic. While we are visiting the caravan, US media is reporting on Trump sending 15,000 troops to the border.

“I see a lot of myself, a lot of my cousins, in those kids trying to get to the US. I just hope they make it. I’m rooting for them.”

Jeremiah

A Preacher from New York

“God told me to come and preach to the caravan but also to preach to the homeless people,” he says.

Although he confesses that he isn’t good at preaching because he has anxiety. He prefers to approach individuals and talk to them about Jesus. But even this is difficult as he doesn’t speak Spanish.

“I hope for them to accept Jesus Christ immediately,” he says.

If he is successful in converting a person, he would join them in a small prayer.

“Jesus Christ. I know I’m a sinner. I accept you in my heart. I like to follow your ways now.”

He tells me that in the first caravan he spoke to a lot of people who accepted Jesus. This second caravan many people are already Catholic.

He has found a lot of the people in the caravan are nice people. But the people in the streets “like sniffing glue to get high”.

Apart from trying to evangelise the people in the caravan, Jeremiah has been offering amateur immigration advice. He has tried to warn them about the unlikelihood of them gaining entry into the US.

“I’m telling them that when they get to the United States and they apply for asylum legally they are going to go to jail and most of them are going to be deported. 99% of them probably. United States isn’t accepting them. So a lot of them are going to go back to their countries anyway. So they’ve just walked all these miles for nothing. If they do it illegally there’s a good chance they’ll be arrested and deported straight away. A lot of people aren’t listening to me.”

When people don’t listen to him he asks them to pray.

“The Bible says if you say a prayer according to God’s will you’ll be answered. If it’s God’s will for them to arrive in the United States and not to go back to Honduras and they actually pray for that and they know that Jesus Christ knows them then God will answer that prayer and they will make it.”

Concepcion Gonzalez

A one-legged man rides La Bestia

After that he lived alone in Honduras selling items on the street. Then he moved to an agricultural area where he worked with his family on a farm where he worked for one year before he decided to join the caravan.

When he made the decision to leave his country he thought the trip would be “all rosey”. He spoke with many people who said that life was “very beautiful in the United States” and that he would live in a “paradise”. He wanted to experience this for himself. In October he left for the Mexico-Guatemala border and crossed into Mexico where he met many people who were following the same road. When people started walking he began to question whether he could walk all the way to the US. It had been a difficult journey and he was already thinking to himself that he would return home. His companions were going to leave him because he could not keep up.

And then he boarded a train for the first time. He wasn’t sure how he would board the train. He was worried that if he fell he would die. Nevertheless, he joined a group who were boarding “La Bestia". When the train arrived, one person shouted: "Now!" And they climbed aboard. He threw his crutches to a friend, grabbed the rails and climbed on top of the carriage.

They stayed on top of the train all day and all night until they arrived in Tierras Blancas, Guanajuato at seven in the morning. From there he took buses all the way to Tijuana.

Jesus

"I saw death in that second"

“The Mexican police stopped us and said we couldn’t pass,” he says. “They closed the border.”

The last time I saw Jesus was in Mexico City. He says it took him five days to travel more than 2,700 kilometres from Mexico City to Tijuana. He took buses day and night, without sleeping and without eating food or drinking water. He says basic provisions weren’t offered by the authorities helping the people of the caravan, nor was there any opportunity to buy. Jesus changed from one bus to another, stopping on deserted highways, until he reached Tijuana. Even if there had been opportunity to buy food and water, Jesus did not have any money.

Jesus has been in town for ten days, his future is uncertain, and he’s restless. He does not want to be stuck in Tijuana. He is tired of sleeping on the ground enduring cold, wet evenings and mornings. He feels locked inside the shelter. His money is running low and he says the local authorities haven’t provided food and water for the people inside the shelter.

He experienced violence from the local people of Tijuana when he was staying in a migrant guest house in the region known as Las Playas. He was with a group of people from the caravan when some locals started throwing stones, logs, and bottles. After that Jesus was transported to the shelter in Zona Norte, the red light district of Tijuana.

“They do not want us here,” Jesus says. “We have to cross.”

The people of the caravan have been offered work in Mexico to encourage them not to try and cross into the United States. Jesus met a man who asked him to work at a carwash. He tells me he will work a few days but he doesn’t want to stay in Mexico because he is worried about his wife and 3-year-old daughter back in Honduras.

“They need me to send them money for food. My wife can not stay like this, alone with my daughter.”

Jesus was kicked out of home when he was 5 years old. His dad didn’t believe Jesus was his son. His biological parents didn’t even get him a birth certificate. Luckily he met a man named Roberto who took a liking to him and raised him as his own. Although Jesus never went to school, Roberto taught Jesus how to be a good, honorable person.

“Since I was a kid I’ve always wanted a family, which is why I married young. I guess that has a lot to do with the fact that I never really had a family I could call my own. And now I have a wife and a beautiful daughter whom I love very much.”

It was difficult for him to leave his family but he had 3 major financial responsibilities which he couldn’t afford: rent, utilities and food. His family was constantly going to bed hungry. When he heard about the caravan he made the decision to make the journey to the United States. He was at work when he called his wife to let her know he was leaving. He knew it would be impossible to say goodbye so he didn’t. He simply went to the terminal where the caravan was scheduled to pass by, knowing he may never see his family again. However, that evening his wife and daughter came to the terminal and waited with him. He tried to console them but the closer the caravan got, the more they cried.

“Saying goodbye was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. What a sacrifice it is to achieve the American dream. I want to find work, and call my family on the phone and say: ‘Look. I am very well, and I'm working and I'm sending you money so you can eat.’ That's my dream. To help them to live a better life. Deep down I am afraid that as my daughter grows up, she will forget who I am and will stop loving me the way she does now. I cannot let that happen.”

Jesus believes in a rumour he heard amongst the people of caravan. If a person has family members in the United States, those family members can pay for the person’s visa and pick them up from the border. He thinks because he has no family in the US he will be deported. He thinks his only option to enter is to jump the wall.

Jesus went to the wall the other night with 12 other people.

“We found a tunnel, a sewer,” he says. “We went through that tunnel until we hit a dead end. The tunnel was sealed with iron bars. We could not pass we had to go back.”

They returned to the Mexican side of the wall and intended to jump, but their attempt was interrupted by a man.

“We looked at the man and he took out a gun. Boom. He tried to kill us. I ran and everyone followed me.”

They ran for about four blocks until a police truck arrived and saved the whole group and returned them to the shelter. Jesus is convinced the man was an operative from a drug cartel.

“I saw death in that second. I felt the bullets. I could feel the slugs in my ribs. But thank God nothing happened to us.”

Jesus doesn’t want to jump the wall to cross into America.

“It's abusing the authorities of the American lands. But if we do not do it, we will never arrive.”

Jesus is worried that it is only going to get more difficult to cross. In the days since he arrived in Tijuana he has seen the US authorities ramp up security on the wall. There are more migration officers, and more security cameras and hurricane wire installed on the wall. Apart from being killed by drug cartels, he is worried about being detained and deported. He doesn’t know for how long he will be imprisoned if he is caught.

“Imagine that we cross over and are caught by migration. All this sacrifice we have made and nothing will be left for us. It's a problem that we have to solve peacefully. We have not come to make chaos. But this will only end peacefully when they invite us to say: "Hey brother, we are going to eat on that side".”

Jesus didn’t try to jump the wall. Instead he returned home to Honduras to be with his family with the help of the International Organisation for Migration.

Protester

Anti-migrant rally in Tijuana

She tells me that the protesters don’t have a problem with immigrants, they have a problem with “invasion”.

“They are not immigrants, they are invaders. They don’t come here to work. They believe they are on holidays. They come to make noise. They don’t appreciate what they receive. They reject what is given to them. They are ungrateful. They are aggressive. They threaten us.”

She admits she has not had personal contact with the people of the caravan but has seen this type of behaviour on the news. Right-wing news outlets have reported that the people of the caravan are discarding donated Mexican beans, a symbolic rejection of Mexican hospitality.

“Like everyone else, we want the caravan to leave. We don’t want them here in this country. Since the beginning they didn’t do things correctly. They entered this country like buffalos, breaking down gates. We want to see if they do the same in the US border. They need to learn that this is not the way to do things.”

This is my first day in Tijuana and these arguments are new to me. Over time, I hear these same complaints repeated by taxi drivers and people in cafes. I continually hear talk of people in the caravan being violent, even though there have been very few reports of such. Perhaps I use different news sources to the people involved in such protests.

Like many people from Tijuana, this protester uses the arrival of Tahitian migrants and refugees as an example of how to behave.

“They came to work. They crossed the border correctly. We don’t have any problems with them. With this caravan we do. We don´t want them here, or in any shelter, or in their consulate. We don’t want them here in any way.”

Haitian migrants started to arrive in Tijuana in 2016. Most came from Brazil where they had found work following Haiti’s devastating earthquake in 2010. When Brazil’s economy suffered a major downturn and jobs became scarce, many Haitians began leaving for the U.S. border. They travelled for months by land all the way to the US-Mexico border, in a manner not dissimilar to the caravan. The story goes that since they arrived in Tijuana, while they wait for entry into the US, they have found work and acted as model citizens.

The woman tells me she is from Tijuana and that this is the first time she has attended a protest like this because it’s the first time Tijuana has experienced such an “invasion”. What’s strange about this protest is that Central Americans, including Mexicans, have been trying to cross the border at Tijuana for decades. What is it different about this caravan is that the people have arrived together, organised in their thousands, which allows people to perceive it as an invasion.

“Why do they come here to do this? Why don’t they do it in their own country? Why they don’t go and protest to their own president? Why do they feel brave enough to do it here? We are not going to allow it.”

The protesters seem to think that the problem is with the way the Peña Nieto government has handled the caravan. They believe the response to future caravans will be different with the incumbent president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, even though Obrador campaigned on a gentler approach to migration.

“These people complain they don’t have anything to eat, so why they reproduce and have children? Why they have children if they are not capable of looking after themselves? Why they reproduce? Do not reproduce!!!”

The protesters roar, “Tijuana! Tijuana! Tijuana!”

Judith Sánchez González

Donates food for the migrants

“For me, this is food for my soul,” she says. “I believe if we are going to do something, we have to do it right. Not the leftovers. They need to be fed.”

Judith brought her daughter with her so she could teach her to be generous and to be kind and compassionate.

“We are embarrassed it wasn’t enough for everyone but that was all we could afford to buy. We do not have money. We work day by day. But we can spare a little bit of what we have. We do it with all our love for them. Tomorrow, with God’s help, we will cook a little bit more and will bring it here.”

Judith came to the shelter as an act of kindness but also as a counter-protest to the anti-migrant sentiment that has been getting coverage on the news. She says she didn’t sleep the night before because she was watching videos of the protests.

“You know what hurts me? What really hurts me is that they put hate and racism in my Tijuana. Where I was born. My land.”

She was born in Tijuana and has lived there her whole life. She believes the people who are acting out against the caravan are migrants themselves.

“Every single day people from all over México illegally cross the border to the United States. So how is it possible people behave like this to other migrants?”

Saul

Anthropology student arranges donations

Saul and his friends are part of a student group that organize themselves to engage in political and cultural and social events throughout the city. They previously helped during the earthquakes in Mexico City last year.

I ask Saul what he thinks of the online commentary criticising migrants for not accepting donations.

“I think that for a process like this very specific things are needed, and it is a little rude that people only donate their garbage. People not be carrying things on their trip that they do not need.”

Saul preferred not to be photographed.

Diana

18-year-old returns to El Salvador

“Like tourists,” Diana jokes and they laugh.

They will join hundreds of people who have elected to return to their home countries with the help of organisations like the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

IOM was contracted by the Mexican government to facilitate the voluntary and safe return of Central Americans who were part of the caravan. Consulting and registration posts were opened in Tecún Umán (Guatemala), Tapachula (Mexico), Mexico City and Tijuana (Mexico).

In the month of November, 453 people (of which 84% were men) requested and obtained the support of the IOM to return to their countries of origin or residence: Honduras (57%), El Salvador (38%) and Guatemala (5%). Twenty-five unaccompanied migrant children returned by air. An additional 300 Central Americans had expressed interest in returning home.

The returns program is funded by the Office of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) of the US Department of State, IOM also coordinates with the governments of all the countries involved to achieve a regular and safe return of all migrants.

Manuel

A volunteer with the caravan

“Most already know the way, some do not know. We just have to orientate them.”

He also advises people about how they are supposed to behave.

“Among so many people there are some who behave well and others who behave badly.”

Manuel says there are 15 volunteers in the caravan; however, that number fluctuates. There are also 20 coordinators who make proposals at the assemblies. He believes the main guides are the Catholic Church and the state human rights departments of Mexico.

Manuel wants Mexico's human rights departments to support the caravan to establish itself at the border and assist people to ask for asylum.

Anton

Guest House worker

Hector Lopez

Deported US veteran

The US has recruited immigrants to its armed forces throughout its modern history. During the War of Independence, Congress authorized the creation of a German battalion in 1776. During the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848, newly arrived immigrants from places like Germany and Ireland represented a large portion of recruits to the U.S. Army. At the beginning of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, roughly 38,000 members of the invading force were not American citizens. By 2018, there were 65,000 immigrants serving in the US military. That number included 18,700 troops who held green cards (legal permanent residents who are not yet naturalized citizens). According to the Pentagon, about 5,000 such residents enlist each year.

Hector served in the US military from 1982 to 1988. He was in the reserves but his unit was activated during the invasion of Grenada.

“I was ready, willing and able to go. Fortunately I didn’t see no combat and I made it home alive unlike some of my fellow veterans.”

Hector was born in Mexico, but lived in US for over 40 years as a legal permanent resident before he was considered for deportation.

“They told me if I served my country I was more American than some Americans. I consider myself an American. I was just born in Mexico. I didn’t have no need for citizenship. I never thought for a minute that I would ever be deported.”

Hector was deported to Mexico after recording two counts of marijuana possession.

“It’s unfathomable. I don’t even like thinking about it. The country I was willing to give my life for doesn’t give a shit about me. They just tossed me out like yesterday’s garbage. The thing that makes it more fucked up than anything else is the fact that if I died right now I could go back to the US in a box and be buried in a veteran cemetery with full military honours but because I’m alive and deported I can’t go back.”

Hector says deportations of veterans began after Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act in 1996. The act made it easier to deport Immigrants — including green-card holders — by radically expanding which crimes made an immigrant eligible for deportation. Hector believes that felony convictions of veterans is often due to their PTSD caused by military duty. He thinks the act took discretion away from judges so they couldn’t consider his military service to the country in his deportation proceeding.

Since 1996, the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana has come into contact with over 100 veterans who have been deported to over 30 countries of origin around the world. All of these veterans had legal residency status, Veterans Administration (VA) Benefits and strong ties to the United States prior to deportation. Many were forced to leave behind families and homes in the United States.

In late 2001, President George W. Bush implemented a new naturalization process for immigrant servicemembers. As a result, any servicemembers with even one day of honorable active-duty service can apply for citizenship, regardless of how long they have been a resident. Since then, more than 109,300 US troops have been naturalized.

Unfortunately for Hector, he was deported long before 2001 but this hasn’t dampened his spirits. He says the state of California is moving to expunge his marijuana convictions so his case is likely to be overturned any day now and he should be returning home soon.

“The ones you see here are very fortunate because we are alive. Maybe not living the life we are supposed to live or we want to live. But nevertheless we are still here. We are fighting for our rights. Not only as Americans but as veterans of the US armed forces.”

Antonio

All his friends in Honduras are dead

He is from a small suburb called Ciudad España in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. The suburb was originally an emergency camp set up for victims of Hurricane Mitch like his parents. Foreign aid from Spain helped with housing development. That’s how his mum got her house, and that’s why the suburb is called City of Spain.

His mum works as a cleaning lady at a school and his dad can’t work anymore after he was kidnapped and tortured. He was burned inside the bus that he used to drive. He survived with scars all over his face and his hands, but he can no longer move very well because his tendons were all burned.

“My dad does look a bit ugly now, all burned up, but thank God he’s still alive and I can still hug him.”

Antonio has 5 siblings: one older brother; the rest younger than him. They are all at an age where they can work which means his responsibility lies with his parents. In Honduras there is no pension plan and his mum is already 65 years old and won’t be able to work for much longer.

“That’s why I came here. If God wills it and everything goes well, this year I will enter the United States. I can get a job and I will be able to help her out.”

Antonio is an electrician, but in Honduras he couldn’t find work and he relied on his mother’s income.

“We call our current president [Juan Orlando Hernandez] Stealing John. Everyone says that his family is involved with the drug cartels.”

Antonio says there is nothing worse than being young in Honduras.

“We live in a constant state of fear. Everyone is scared. When a police car passes by you hide because it could be the death squad or corrupt police. Young people like me in Honduras we always think about death. How are we going to die? Who is going to kill us? When is my time?”

Almost all of Antonio’s friends from school have been killed. Some of his friends became involved in the gangs and their bodies were found cut into little pieces, bagged in a sack and thrown onto the street.

“Thank God I’m still here. I want to grow old but it’s not easy in Honduras. That’s why I’m looking for a better life.”

He has been with his partner Tina for 3 months. They were friends for 6 years before they became lovers.

“Tina is a gift from God. Tina is the most amazing thing that has happened to me in all my life. There have been a lot of women but I think Tina is the last one you know? I think I have found my other half.”

Antonio and Tina didn’t join the caravan until the town of Arriaga in Chiapas, Mexico. They couldn’t leave Honduras until they had raised enough money to make the trip.

It hasn’t been an easy journey. There have been disagreements within the caravan, but Antonio attributes these arguments to hunger and fatigue. Sometimes they were able to catch a lift with buses or trucks but they have walked most of the way.

“Thank God for the Mexican people who have fed us, clothed us and cared for us when we were sick. We are very grateful.”

Despite these hardships, Antonio remains positive and enthusiastic. He has an indomitable spirit. When we went swimming at the beach in Tijuana, I taught him how to bodysurf a wave.

“It was spectacular,” he said afterwards. “I felt like I was flying. I felt like a comet in the air.”

Then he made a flying sound and laughed.

While on the road, Antonio and Tina met a group of other Hondurans and they now travel in a group. Antonio calls Pedro and Vincent his “brothers” and Vincent’s one-year-old his “niece”, displaying his warm of character.

He thinks people join the caravan because they feel protected by the human rights organisations who march with them. That’s why people took the opportunity to travel with women and children.

Antonio’s mother didn’t want him to make the journey.

“When I said goodbye to her and told her I was leaving, she started to cry like a toddler and that really hurt my heart. It broke in half.”

One day, Antonio answered a call from his mother. She was praying for her son that everything went well, but she was also crying with fear for her child.

“We are all scared of what’s ahead,” Antonio says. “But if you don’t learn to face your fears you will never beat them. You will always be paralyzed. My family has always told me there are two types of faith: one’s alive and one’s dead. I am here, risking my life, and that is an alive faith. I know that God will look over me as he has been doing up to now.”

Antonio wants to work in the United States, but he wants to learn English first so he can have better job opportunities. He wants to return to Honduras with money and run a motel. He’ll use the profits to help his family pay off their debt.

He believes the United States is the land of opportunity and law. In Honduras, the only people with opportunities are people who work in the government and their families.

“I believe that in this world there are good people and bad people, no matter where you are. But there is racism in the United States against Latino migrants because we are viewed as cheap labor.”

Even so, he is prepared to live with racism and oppression to achieve his dreams.

“I have endured the cold, I have endured hunger but my health is good. I’m still strong and that’s what matters.”

Tina

Left behind two children in Honduras

“I love my children with my whole heart and with my whole being. They are the only good thing I have.”

Tina’s parents split up when she was three years old. Neither of her parents wanted to take care of her, so she was raised by her aunt until she was 12 years old and in the 6th grade. Her mother spent her time with other men. Her dad was the kind of man who was more interested in the women he was with than his children. He didn’t even care if his children had shoes. Her uncle and aunt cared for her even though they already had 6 children of their own. When she tells her story, she laughs at the darkest moments trying to make light of her hardship.

She met the father of her children when she was 15 years old. She thinks that the relationship was always broken.

“I was too young I think.”

He was an alcoholic and he was impulsive and jealous. He never hit her but he did abuse her psychologically. He used to say no one else would love her because she was ugly.

“He left on the 7th September 2012.”

He now lives in Miami but they still talk over the phone.

When she was younger, she believed in love. But now she finds it hard to believe or trust people. She doesn’t believe people when they say they love her because she has failed in love so many times before. Now she believes in good moments and she tries to enjoy those moments with people as much as possible. She thinks people stay together for as long as it suits them.

“That’s why I can’t love anybody. Except for my kids,” she says and laughs. “From when they were born, I made sure they had what they needed. As long as they are well, I am well. If they eat but I can’t, that’s okay. Nothing else matters.”

She’s been with Antonio for 3 months, but they were best friends for 6 years before they got together romantically. Tina knew a lot of Antonio’s former girlfriends. She used to lend him her bedroom. And he would look after her children when she needed a break from motherhood. They were confidantes.

“Antonio is beautiful. He’s really special. But he still has some issues with jealousy. And I think I am a bit bipolar. I am angry.”

She used to swallow her issues until it hurt. She went to a doctor who told her that she needed to speak about her problems or eventually she would have a heart attack. So now she tells Antonio when something bothers her about him and he puts up with it.

“When Antonio tells me that he loves me, I don’t believe him. I tell him that he should find someone who knows how to love back. Because I can’t.”

She has always wanted to travel. But until she joined the caravan she had never left Honduras. The caravan was an opportunity that she couldn’t ignore.

Traveling alone with Antonio for such a long time has been stressful.

“There are days when I say that I want to be alone. I have a headache. Go away! And I escape,” she laughs. “I escape because I’m used to being alone and at this point in my life to have someone with me all day is really stressful.”

She likes to be solitary. But she also likes to have Antonio around because he listens to her and offers advice.

Her refuge in the past was working. She has worked since she was 15 years old. Her first job was in construction assisting builders. She also made and sold street food and has cleaned houses. She always wanted to be an engineer but she never got the opportunity to study. Every day she would leave her house at 5.30am and return home at 7pm.

“That has been my whole life. I’ve never had the time to enjoy myself.”

When Antonio told her about the caravan, the news coincided with her being let go from work.

“In Honduras, if you don’t work, you don’t eat.”

In Honduras, she lived in a house owned by the father of her children. He would regularly threaten to kick her out. She has always wanted her own home. After she heard about the caravan she withdrew her life savings (6000 lempiras; US$245) to make the journey with Antonio. She didn’t have enough money to bring her children. She could barely afford her own passport. The children are being looked after by a good friend of hers.

Even if she had enough money, she didn’t want her children to suffer on the journey. She had previously tried to enter the US with her children using a smuggler.