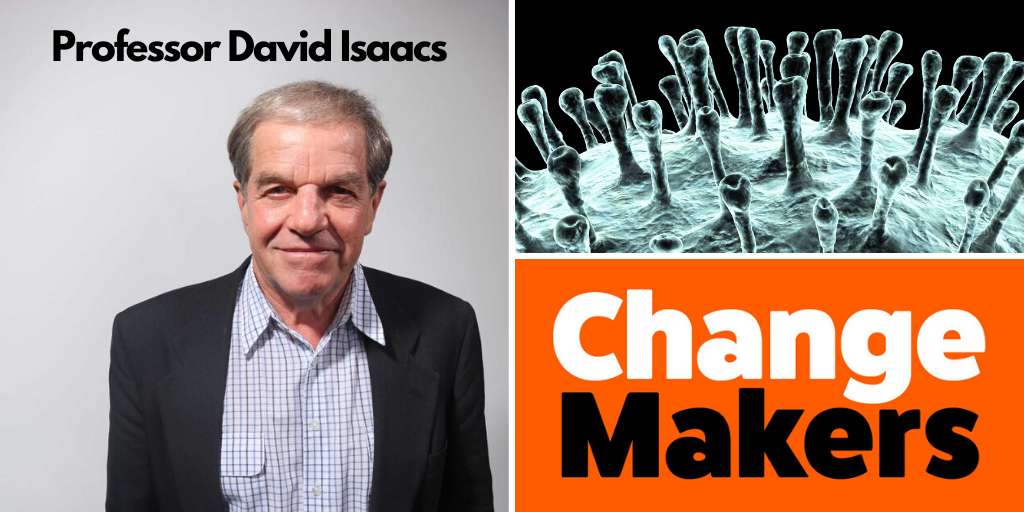

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, there has been an overload of information on social media and news sources. Often it’s hard to know what is good advice and what is misinformation or hysteria. I decided to speak with a trusted source to get the real deal behind the pandemic. My dad, David Isaacs, is a consultant paediatrician at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, and Clinical Professor in Paediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Sydney. He has been a member of every Australian national immunisation advisory committee for the last 25 years.

This is an edited recording of our conversation. There will also be a Changemakers podcast episode about the coronavirus pandemic which will be available in the coming weeks.

I posted the edited transcript of the conversation last week which received positive and widespread feedback, as well as lots of questions. I have now added more information to the article as a result.

It is important to remember that this pandemic is a rapidly changing phenomenon and the information provided in this conversation was accurate to the best of David’s knowledge and the data available at the time of the interview.

Follow me on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter for regular updates on the pandemic from Professor David Isaacs.

TRANSCRIPT

MARK

Alrighty, David, do you want to introduce yourself, please.

DAVID

So my name’s David Isaacs. I’m a pediatrician, children’s doctor. And my special area is Infectious Diseases. And I suppose immunization as well.

MARK

Didn’t you just write a book about something like this?

DAVID

Thank you, Mark. Nice plug. Yes. I just wrote a book called Defeating the Ministers of Death about immunisations, it’s just been published by HarperCollins. About the history of plagues and pandemics and then the way we’ve developed vaccines to control them.

WHAT IS COVID-19?

MARK

What is COVID-19?

DAVID

COVID-19 is the name given to the disease, not the virus, caused by the novel coronavirus. So C-O is corona, V is the virus and I-D is the infectious disease. And it started in 2019 right at the end of the year. So the name for the virus is SARS CoV2. The virus is related to the virus that caused SARS, which was also a coronavirus. They’re sort of cousins. So you may hear them used interchangeably, but actually SARS CoV2 is the virus, COVID-19 is the disease. It’s called a corona because when you look at it under the electron microscope – you can’t see viruses except under incredibly high magnification, many thousand fold – and when you look at it there it’s got a crown or a halo round it. And we’ve known about them for 50 years as being a common cause of common colds or – not as common as rhinovirus – one of the causes of a common cold in children, young adults. Occasionally they cause a bit of wheezing and occasionally a bit of pneumonia, but really not very severe infections at all. And then suddenly, out of the blue in 2003 came a disease called SARS, which is a severe respiratory infection with pneumonia. And that came in China and Singapore, Hong Kong, and had a very high mortality, actually interesting, higher than the mortality of COVID-19, but was limited in its spread. So it didn’t spread to the rest of the world, although we were scared it would. Since then, there’s been a virus infection called MERS, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome. Now, all of those corona viruses, SARS, MERS and the new virus, the novel coronavirus, probably originated in bats originally. So they’re viruses that infect bats, don’t seem to do them much harm. They don’t drop out of the sky with infections, but they’re in the bat population and then somehow they get to humans. Usually there’s what we call an intermediate host. So for SARS, interestingly, it was the civet, which is a sort of wildcat. Civet. C-I-V-E-T. For MERS it was camels. And people got MERS when they went to the Hajj in Mecca and so on in Saudi Arabia and they would get coughed on by camels. And that was one way that we think that they were infected. In the case of SARS CoV2 or COVID 19, it seems as if the original first few cases in China occurred in a seafood market, an open-air seafood market, and they don’t just have seafood in a seafood market, they have bats and things are sold there as well. And how it got to humans we’re not quite sure.

PANDEMICS

MARK

What is a pandemic?

DAVID

A pandemic was an epidemic, an infectious disease that spreads around the world. Pandemic just means it’s widely spread, spreading all around the world. Pan is everywhere. And so an epidemic is spreading locally, say, within a country or within a region. And a pandemic is when it’s much wider spread.

There’s quite a lot during the book about nature being the world’s greatest terrorist. And that pandemics such as the Spanish influenza at the end of the First World War killed 50 million people, more than both world wars combined. Nobody knew how to make an influenza vaccine and it controlled itself because eventually so many of the population have been infected it can no longer spread. And at that time, it was about 500 million of the world’s 2 billion people we know were infected or we’re pretty sure were infected.

There are influenza pandemics about every 30 or 40 years of varying size and the difference in the size from one epidemic or one pandemic to another is how infectious the virus is and how severe it is. Flu comes around every year, changes a little bit, and our past immunity helps us a bit. And then suddenly along comes this new flu. So that’s the pandemic flu about every 30 or 40 years.

The bird flu has jumped, occasionally jumps to humans, but doesn’t spread from human to human much. So it’s not proved as much of a problem. And a disease becomes a problem when it can spread readily from human to human.

So the swine flu is thought to have started in Mexico, it was said, although it might have been elsewhere and was caught from pigs. We’re pretty sure. Interestingly, so, almost certainly, was Spanish flu. The one in 1918, almost 100 years earlier. It was also probably caught from pigs. And so in 2009, it was called pandemic influenza. We’d been waiting for a pandemic, thinking it would come. It certainly spread to lots of countries, but it wasn’t nearly as severe as we had feared. And we now have a vaccine against that, the 2009 swine flu. And now that’s part of our routine immunisation all round the world is to include swine flu in that vaccine.

THE CORONA PANDEMIC

DAVID

Initially, it wasn’t clear whether this was going to be a pandemic, but it’s now affected almost every country in the world. So it’s definitely a pandemic. Why did SARS not become a pandemic and just became an epidemic? Remember SARS was in 2003. The answer seems to be that if you got sick with SARS, you weren’t maximally spreading the virus until you’d really got quite unwell several days into the illness. So it was quite easy to identify people who were really quite sick. Say, “oh, they’ve probably got SARS”, test them and then isolate them from everyone else. The difficulty with the novel coronavirus, the one that’s causing this current pandemic, is that people seem to be much more infectious, much earlier in the illness. So they’ve really only got a sniffles or even no symptoms early in the illness and they’re already passing it on to other people. So it’s much harder to control. And that’s meant that people have traveled who were not feeling particularly unwell and then they’ve started spreading it in other countries. And then countries have reacted to that with a varying degree of speed. So Australia actually was banning travel from Wuhan and then from China before the World Health Organization said that we should. So Australia actually acted quicker than the World Health Organisation was recommending. Most other countries didn’t. So to some extent, we’re ahead of the game in Australia.

TRANSMITTING THE VIRUS

MARK

Okay Davey, how is the virus transmitted?

DAVID

Corona viruses are basically respiratory viruses. You breathe them in through your nose, possibly you inhale them through your mouth and into your lungs, your upper airways. You can get some respiratory viruses by rubbing the virus, virus in secretions, into your eyes, which is why people wear goggles to protect themselves from these viruses. It’s not thought to be swallowed. So people who think that you eat the bats and that gives you, that’s not right, almost certainly. It must be something in the preparation of the bats that causes it to form droplets and you then inhale those droplets. So it’s inhaling, not ingestion, we think.

The people we know are most vulnerable are people over 80 – you might even say over 70 as well – but older people and then people with what we call co-morbidities. Things like type 2 diabetes, prior severe lung disease and so on. Not asthma, but people with things like we call bronchiectasis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD. Those are the people at greatest risk.

There are some reassuring things about the virus. Pregnant women seem to be relatively mildly affected. They get it about as badly as any other woman of that age. Not worse.

Children very rarely get very sick. So, for example, in the whole world, there’s not a child under ten who’s died from the infection. And very few who’ve got very sick from it under that age. As to why that is nobody’s quite sure. But we think it’s because as you get older, you respond more vigorously to infections. And although children seem to respond well enough to get over the infection, they don’t over-respond. And so the older people may actually be over-responding to the infection and to a certain extent, it’s their own host immune response that does some of the harm.

But there are children as young as toddlers getting infected but not getting very sick at all, so there have been a very small number of cases of newborns catching it from their mother soon after birth with no symptoms at all. So people were worried that newborns would get infected, but they don’t seem to get it. Now, that’s unusual because newborns are very susceptible to infections and to getting very sick from them. So, again, that doesn’t seem to be a big problem. Newborn infections certainly doesn’t seem to be a big problem.

MARK

What’s the easiest way to prevent transmission?

DAVID

Okay, so, it’s in droplets and so you find ways of avoiding droplets. For the common people, we’re talking about social distancing or physical distancing because we don’t want to be anti-social, but physical distancing. Staying a metre and a half apart because the droplets don’t go very far. Wiping down surfaces so that you don’t touch surfaces that might have been contaminated by someone else and washing your hands. People are terribly worried about having little alcohol sprays. They’re great if you’ve got them, but handwashing with soap will work perfectly well. This is a virus that has an envelope around the outside of it made of fat, lipid layer, and fats are notoriously susceptible to soap. So soap and water really works very well.

There’s very little evidence of it spreading on clothes very much. So it can stay on surfaces such as cardboard interestingly and things like that for up to two or three days, this virus can stay alive. But on clothes, it doesn’t stay very long.

We talk about wearing masks if you’re sick or avoiding other people, if you’re sick, if you’ve got respiratory symptoms. I mean most of the initial transmission seems to be within families. But social gatherings, you can get transmission there as well, which is why people are saying to avoid social gatherings. There’s increasing pressure around the world to reduce social contact with lots of people.

Outdoors there’s likely to be much less spread. Indoors in an auditorium would be much more likely to spread it. It won’t spread in the water. If you swim next to someone who’s got the infection and coughs and splutters on you, then you could get it by swimming next to them. But it’s not under the water or through the water or drinking the water is not going to be a mode of spread almost certainly.

MARK

Why are only sick people being asked to wear masks and not everyone?

DAVID

Oh, that’s in case you ran out of masks. If you have limits in the amount of personal protective equipment, including masks and the best masks are expensive and in fairly limited supply.

WHAT HAPPENS IF YOU’RE INFECTED

MARK

What happens if you’re infected?

DAVID

If we’ve got somebody that we know is infected, we test their secretions until they’re clear and we don’t let them walk around. The virus takes two to 12 days to cook and then it’ll show itself. After two weeks, if you haven’t got sick, then you haven’t got infected. Almost certainly. If you’re infected, you can shed the virus for anything from a fairly short time up to a matter of more than two weeks. So if you’ve been very sick with the virus, you often keep the virus there for quite some time. And those people we don’t allow out of isolation until they have cleared the virus and we check them. Once they’ve cleared the virus, they are then immune and they’re not chronic shedders of the virus.

MARK

What do you when it’s a serious case?

DAVID

The most serious ones will end up in intensive care on a ventilator. Why a ventilator? Because they can’t breathe for themselves because their lungs are all clogged up. They can’t shift oxygen and they will die from not enough oxygen to the brain unless you do it for them. One of the problems here is that even the ones that are going to get better, they remain on the ventilator for a long time. So then ventilator beds get used up a lot.

And in Italy, they’ve actually had the ghastly situation of being, having people having to make decisions about which patients should go on a ventilator because they haven’t got enough ventilators. That is the worst decision anybody in intensive care can ever make if they think someone could survive from a ventilator, but they haven’t got a ventilator for them. Now, that is what all the rest of us are trying to avoid, is ever getting into that situation where we haven’t got enough ventilators.

I think we should just have to be optimistic that by flattening the curve we’re not going to be in a position where we ever have to make that decision about who should and who shouldn’t go on a ventilator.

MARK

Once you’ve become infected and you’ve recovered from that, can you become infected again?

DAVID

Most people think that’s highly unlikely and there haven’t been re-infections that we know about. But if you look at other coronaviruses and there have been a few in the world before. Re-infections are very uncommon; with the same strain they almost never occur. So we would expect, like with measles, you’ve had it once, you will never get it again. We’re not absolutely sure, but that’s what we think.

Most of the evidence so far suggests it doesn’t mutate itself very much. This virus would have the potential to mutate if it stayed within people for weeks and weeks and weeks. But it doesn’t seem to. It has mutated from a previous virus, probably SARS, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate within humans.

HERD IMMUNITY

MARK

Can you tell us more about herd immunity and the British government’s idea of trying to use that to protect themselves against the pandemic?

DAVID

Herd immunity is the idea that when a certain proportion of a population is immune that the virus or the disease can no longer spread in that population, there just aren’t enough susceptible people for the disease to spread. And you can get that herd immunity by everyone having had the infection, as you just talked about with Spanish flu in 1918 when almost everyone had that infection, or the herd immunity can be through immunising everyone. So, for example, measles can’t spread in Australia very much at all because so many of our population, over 95 percent of our population are immune to measles through immunising them so that if someone comes from overseas with measles, one or two unimmunised people might get infected, but it no longer spreads. We have herd immunity. Our herd is protecting the weak, if you like. So that’s the concept of herd immunity.

So the UK had this idea that they could just let the population get infected and it would all blow over. And so once 60 percent of the population were infected, the epidemic would be over because there would be herd immunity then and the disease wouldn’t spread anymore. The trouble with that is if you just let it spread at any rate that it wants, this is a virus that every person that’s infected infects two to three other people. And if you get that doubling every few days, you actually get overwhelmed with the numbers of people getting infected. So if you think of 60 percent of the population of the UK getting infected, UK’s got 70 million people, 60 percent of them is 42 million people. Even with a 1 percent mortality, that’s 400,000 deaths. And if that happens very quickly, the mortality is more likely to be well, currently in the U.K., it’s 5 percent. So that would be an estimated 2 million deaths in the UK, if they’d just let it go on like that. So they’ve suddenly realized that idea of just letting the disease rip and getting herd immunity that way was a bad mistake and a bad suggestion, bad miscalculation. And they’ve changed now and they’ve isolated everyone.

FLATTENING THE CURVE

MARK

Can you explain the concept of flattening the curve?

DAVID

People talk about flattening the curve. So what they mean is that as if you think of the curve as being the number of people getting infected over time, if they’re getting infected very rapidly, then of course there’s a lot of pressure on intensive care beds. If they’re getting infected more gradually over time, then the healthcare system is likely to cope much better.

You need about 60 percent of people to have been infected with the novel coronavirus before it’ll stop spreading in the population. And 60 percent sounds a heck of a lot of a population, it is, but a lot of them will have very mild disease or be completely asymptomatic and yet have been infected and therefore be immune and not be able to pass the virus on.

What we’re trying to aim for is that we get 60 percent of the population will eventually have been infected, but they are infected not too quickly, because if they get infected very quickly, as they are in Italy or in China early in the epidemic, then that overwhelms the health system and you get more deaths because the health system just can’t cope with so many people in intensive care at once.

The aim will be that it takes about six months and sufficient people in the population will have been infected to make spread, much less common, if at all. The ideal would be that it would spread to the people best able to cope with it – the younger people perhaps within the community – and you would protect the most vulnerable people.

HOW TO FLATTEN THE CURVE

MARK

So how do you flatten the curve?

DAVID

What we have now available to us in slowing the curve is trying to decrease spread, trying to reduce contact between people who may have the infection and other people. And we’re particularly keen to protect the elderly and the people at highest risk. And they are the people who should self isolate the most.

In a pandemic when you are trying to limit spread, you have to work out ways that limit spread and don’t impinge too greatly on normal civil liberties. It’s a delicate balance between what’s best for the individual, what’s best for the country.

Now in some parts of the world where they don’t have civil liberties in the same way that we have it’s probably easier for the government to say we’re going to send everyone home for two weeks, you’re not allowed to speak to anyone, to touch anyone. You object, you go to prison, there are terrible penalties.

We’re also keen not to put in measures that might be counterproductive, making everyone work from home and be at home actually increases anxiety. And the evidence from the SARS outbreak that it leaves people very stressed and increases post-traumatic stress disorder sometimes for years afterwards. So it’s not a benign thing to do to shut everyone away and say, just don’t talk to anyone else. It has social implications. It has mental health implications.

Being scared of the virus has effect on people’s mental health, and people will suffer from that. From the fear of it as much as there will be some people who will die from it. There are studies showing that if you put people in social isolation because of a pandemic like SARS, that has a profound effect on their mental health. Both at the time that they’re there, but for months or even years afterwards they are more anxious than people who weren’t put in isolation. So now that may be because the ones that are put in isolation are more likely to catch the disease, maybe they really do have more to fear, but it lasts afterwards. And those are the sort of things that we as a community have to try and deal with by helping people, the most vulnerable people, the people whose mental health is most at risk, and those are people with preexisting mental health problems, including people seeking asylum and refugees, I may say, who are at particular risk.

THREATENING OUR WAY OF LIFE

MARK

In what ways does this pandemic threaten our way of life?

DAVID

So I think it doesn’t just threaten our physical health, it threatens our mental health as well. And there is a great deal of fear around the unknown. And then a new agent that you can’t see that spreads from person to person is a frightening concept. For adults and the elderly, it’s scary. And they’re scared about what’ll happen to them. They’re scared about what will happen to their relatives. They’re scared about what will happen to the economy, which is also in huge trouble from this. And that’s not my area. I won’t talk about the economy in this, but I do. Well, I just did. But anyway.

There are some 20 year olds, 30 year olds, 40 year olds, 50 year olds dying from this infection. It is scary. The only people who can really be pretty certain they are not going to die are children under 10 because there haven’t been a single death of a child under 10. But on the other hand, we live with the risk of death every year. There are thousands of deaths from flu every year in Australia, mainly in the elderly. And we may never reach as many deaths in Australia from COVID-19 as we do from the flu every year.

And part of what governments try to do is to calm people down, say, don’t be so frightened. Angela Merkel’s just done that. And she was brilliant at it. In terms of talking to the German people about the things that they were doing, trying to explain how they were trying to cope and look, we’re all in this together and we’ll try and work together, have solidarity in trying to deal with it.

So, I think we all have to find ways of coping with being a bit overwhelmed by this. It’s everywhere. It’s in all the news. It’s all the conversation is about at the moment.

MARK

Do you think social media escalates the panic?

DAVID

That’s a difficult question and I’m not sure that I can answer that.

MARK

That’s because you’re not on social media.

DAVID

I don’t do social media very much. But people have looked about it, about vaccine fears for routine immunisations. And there is some suggestion that social media amplifies the discussion, whether it amplifies fears, I think it can certainly. I mean, I think it’s got the potential, but there’s also the potential for social media to be extremely helpful. You know, even grandparents are using social media to talk to their grandchildren rather than seeing them face to face. So, social media has the power to be a real force for the good, as well as being potentially fueling fears.

AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

MARK

How has the Australian government responded to the pandemic?

DAVID

The government is seeking best advice. It’s got an expert committee that advises them every day on which measures to use. Our government has a chief medical officer and the government is bound to follow what, in this case it’s a man, what he, Dr. Brendan Murphy, says. Brendan Murphy is a good man, he’s a good, sensible public health physician and he immediately got round him a committee. AHPPC it’s called if you want to look it up. The names haven’t been published because almost certainly they will be attacked in social media and it would make their lives a misery. And that’s not fair on them.

The AHPPC advises him every day on what they should do based on the current figures, based on what’s going on around the world, and says what measures should be put in place and how much testing should be done. But they are working night and day and keeping up with the literature, advising the government. Brendan Murphy takes that advice, synthesizes it, makes recommendations to the government and by and large, the government is sticking with what they are saying.

The government then publishes information from the AHPPC on the Australian Government Department of Health website. So if you want to see what the AHPPC say, they are the experts. And to my way of thinking, that’s who I trust. And I think that’s who we should all trust. We should be wise on that. They won’t make perfect decisions. Nobody can. But they’re making considered decisions based on the best evidence available to us. And that evidence is Australia-specific. It’s informed by experts all around the world. These people know all the experts all around the world. If that committee says it’s not yet time to shut the schools, that is a considered decision. It’s not a random decision based on no evidence, as some people seem to be saying out there. This is a very, very considered decision and I trust them. And I think everyone else should trust them.

MARK

What do you make of the critics who are saying things like, why haven’t we got more tests?

DAVID

We’re testing as many as we can. There is a capacity. You know, the hospital where I work, the adult hospital next door is doing fifteen hundred tests per day. And the tests take four to six hours each. They’re at capacity. You can imagine, you’ve got to get staff to do it. And staff are working much, much harder than they ever have before. They’re working long hours, working during the night to do testing. And then you also have to have the kits. You can’t do the test if you haven’t got the kits. And everyone around the world wants the kits to do it.

There’s a global shortage of tests. Australia is testing, we’ve done over 100,000 tests. Of which about 0.5 percent are positive, one in every 200 tests are positive. So people want to test more people, including people at lower risk of the disease. Everyone wants to get tested. Then we won’t have enough kits for the people who are really likely to have the disease. That’s not helpful either. So you’ve got to let the experts try and make expert decisions.

We have plenty of critics, armchair critics. They may be doctors. They may be ex-doctors. Now, media personalities. They may just be commentators in the media. They may be the general public. They all seem to think they know better than the expert committee. I don’t think it’s helpful to be sledging government decisions at this moment.

Angela Merkel has made a phenomenal video in which she says, let’s all be in this together, let’s count on solidarity. Let’s support each other. Support the weak. But also she’s saying there’s an element of trust in this. You just have to trust that we’re trying our best and doing as well as we can and criticising it isn’t necessarily very constructive.

MARK

Do you think there’s a space for constructive criticism?

DAVID

There should always be a space for constructive criticism, and there is the ability to do feedback, but constructive criticism is not what I’m hearing a lot of the time in the media. It’s rather judgemental, simplistic, accusatory. A lot of that sort of stuff and I don’t think that’s terribly helpful. And it’s done by people who don’t really know. The questions are asked in a way that imply that they know better than the person giving the answer.

MARK

Do you think part of the reason why sections of the media are being so negative and why members of the public are being so negative is that there’s a lot of distrust in the government?

DAVID

I think that part of it is that the media likes to be sensational and that sells stories. Part of it is that there is a lack of trust. And we know that this is a government that has wisely trusted experts in this situation and during this pandemic. But it’s a government that has systematically rubbished experts in other fields like climate change and so on.

OTHER COUNTRIES’ RESPONSES

MARK

So why were China and Singapore, for example, so effective in shutting down the pandemic in their countries?

DAVID

Both countries introduced draconian measures to control the outbreak, which would probably be not acceptable in Australia. People staying in their homes, having food delivered, not intermingling at all. The place was deserted for weeks on end until the infection came under control.

There are people making political mileage. You can always think that they’re going to be mischievous people calling it the Chinese virus and blaming China for the way they’ve gone. But I think China have done pretty well. I’m pretty impressed with them in this whole outbreak.

They had some 3000 deaths in China in a short period. But since then, it’s come under control. Their epidemic lasted two months. But I think actually the way that they have dealt with it within their own population has been amazing. If you think, as I say, of the population of China, 1.4 billion, and they’ve had some 3000 deaths, and Italy has already surpassed that with a population the fraction the size of China, and has already soared past the Chinese number of deaths and hasn’t stopped yet in Italy, you can see how well China coped.

I’ve heard people say Singapore was really well prepared for a pandemic. They just activated all their planning things and look how well they’ve done. But that’s because they got a horrible time with SARS and they’ve enacted things to try and prevent that. But that’s been very, very vigorous quarantining of people or isolating of people and identifying people very quickly. They were very quick to realize how many tests they needed to do. Doing lots of tests, limiting travel very, very quickly into Singapore. And interestingly, not closing schools.

Australians would and many parts of Europe would just not accept those measures as being for the public good and would either not obey them or I think there would be huge concerns about that. Countries have different levels of democracy, different levels of social control by governments. They also have different aged populations. They have different borders. And so some countries are more islands, if you like. We’re an island. We’re in a lucky position to that extent and are better able to control the flow of people into the country. Some people are naturally blasé about things and all go to the beach or go to the whatever when they’re told not to.

In Portugal, the day they told everyone to work from home, the beaches were completely crowded and then we did it ourselves here in Australia and Bondi Beach was completely packed on a day when everyone was meant to be working from home.

Italy’s in a disastrous state at the moment. You know, it would be petrifying to live in Italy at the moment, I think. You know, they’ve already had more deaths in Italy than the whole of China. And not looking like stopping any moment now. So Italy is in trouble over this. And that’s because they didn’t react quickly enough to the epidemic.

If you refuse to test, as Indonesia did for a bit, funnily enough, you don’t find any cases. And of course, you can lull yourself into a false sense of security. And then suddenly the epidemic is on you. And people think the United States are in that position. We know that some cases in Australia came from people traveling from the United States who weren’t known to have COVID-19.

You would want a very good public health system here. I think this is going to highlight how good public health, having the government responsible for your health is terribly important. And I think countries that largely have private health with its inequities will find that poor people and the elderly will be at much greater risk.

DAVID

So the countries that have been overwhelmed like Italy their mortality in Italy is about 10 percent. That’s incredibly high. The mortality in Germany is less than 0.5 percent. So 20 times lower than Italy. The mortality in Australia at the moment is less than 0.5 percent, 20 times lower than Italy. All the deaths in Australia but one have been people over 70. It was one person over 60 who has died, but the other 13 of the 14 deaths have been in people over 70. I think the UK is heading for quite a nasty outbreak and I think the US is heading for quite a nasty outbreak. The numbers look like they’re doing that there. They may have reacted in time and it won’t be as bad as Italy and Spain, but I think both countries there’s a risk that it’s going to be pretty bad.

MARK

Do you think the world was prepared for a pandemic?

DAVID

Absolutely. The world has been talking about pandemic preparedness, you know, there are documents from the World Health Organisation, and everyone. The difficulty with preparing for a pandemic is that a pandemic, by its very nature, is unpredictable. It’s going to be unpredictable because each virus is different from each other one. You can try to plan for them as much as you like. But when it actually happens, the speed of spread can still cause huge problems.

VACCINES

DAVID

So one of the first things that we try to do is develop a vaccine if we know how. And it takes us some months to develop a vaccine. I mean, maybe in future we’ll be better at developing vaccines quicker for situations like this. We will have learned from this outbreak. There will be a vaccine against this SARS COv2 within a certain amount of time.

MARK

What’s happening with developing a vaccine now?

DAVID

Oh, lots of people are developing vaccines. But we’re a few months away from having an effective vaccine.

MARK

And once that comes in will it stop the pandemic?

DAVID

Well, I mean, it depends how effective the vaccine is, doesn’t it? And it depends whether it’s necessary. So as I’ve said, SARS, the vaccine was never really needed because the disease disappeared and hasn’t recurred since 2003. Now, whether that will happen with this illness, we don’t know. It’s a different disease, although it’s related. And I would think we might well need a vaccine.

If there was a vaccine available now, we’d be giving it very widely. As long as we could manufacture enough of the vaccine. And you would give it to the people who are the most vulnerable. So you’d have to prioritise who were the people who most needed it. The difficulty is that we do not think a vaccine will be available for 6 to 18 months. And by that time the disease may have burned itself out as SARS did. It may not, in which case we’d desperately need the vaccine. And that’ll be a question of how much we can manufacture, how much it will cost, who could afford it.

ANTIVIRALS

MARK

What is an antiviral drug and do you think it’s effective in treating the virus?

DAVID

The way that viruses replicate is to take over the host DNA or their host nucleic acid and sort of persuade the host to make the viral particles. It’s a parasite, if you like. It manages to manipulate hosts and to get them to do the work, to make the viruses. And there are ways of interfering with that system, if you like, that prevent the virus replicating in that way.

And so the sort of antivirals, there’s one called acyclovir that’s used for chicken pox and herpes simplex virus infections. There are very effective antivirals against HIV human immunodeficiency virus that were developed. One of the ones that people are looking at is a drug that was developed for Ebola and turned out not to be effective in Ebola. And then people were looking at it in SARS before SARS went away. That’s a drug called remdesivir. People have looked at agents that modulate your immune response, because the worry here is that this is the immune response doing some of the trouble. But we haven’t got antiviral agents known to work against coronavirus. I don’t think anyone would quite know how to develop a new antiviral that was specifically targeting coronavirus. I don’t think we have worked that out yet.

SHUTTING DOWN SCHOOLS

MARK

In Australia we’ve had a lot of people demanding we close schools. What do you think of that?

DAVID

Shutting down schools is controversial because children don’t seem to get nearly as sick with with the virus, if they get infected. They seem to get infected, we think, about as often as adults, but not nearly as sick. Many of them seem to be asymptomatic, even if they’re infected. And then they clear the virus and they’re immune. We don’t know if they pass it on when they’re infected and asymptomatic those children, but we think they’re not big spreaders of the virus.

There are no cases documented where an adult’s caught the infection from a child. When I say documented, I mean, nobody has written up anywhere in the literature where a child had it and that was the only person and then the adult definitely got it from the child.

That’s not the only infection that does that. There are other infections where children do not transmit it to adults very much, if at all. Tuberculosis is one. Adults give it to children. Children don’t give it to adults. Different disease, but still, it’s not unheard of that you have children, not as big transmitters. And the previous coronavirus, SARS, that was again, children were very rarely infected with that or very rarely got severe disease with that. I couldn’t find a single report saying teachers were increased risk. But that doesn’t mean they’re not. So that is why in Australia, the government’s going on saying, on advice, on medical advice, that closing schools would not be beneficial.

If you close down a school that has knock on effects on. Who looks after the children? What happens to the parents who should be in the workforce? Are the children likely to expose other people more like grandparents and so on? And what will happen to the teachers? They then become unemployed. May never get their jobs back.

There’s a great outcry saying we should have closed the schools earlier. And I think our decision not to close the schools was a difficult one. But is a considered one. It’s not a flippant one. It’s one that was made in the light of the best evidence of what’s happening in Australia.

MARK

What about families with older or immunocompromised family members?

DAVID

People who are at high risk, and as I’ve said, you know, the elderly and so on, those people, you should try and protect them as much as possible. If you are in a family where you had a child with cancer that family would be worrying hugely or an adult with cancer. People would be worried hugely about whether their medication was immunosuppressing them enough to make them vulnerable. There’s a fair amount of advice on that and they should be asking their cancer doctor basically because different cancer drugs immunosuppress people to a greater or lesser extent.

MARK

Some children are also in vulnerable demographics such as indigenous kids, disabled kids, immunocompromised kids?

DAVID

We haven’t yet had any cases in indigenous population and obviously we’re trying to keep it out of the indigenous population, particularly in remote areas. There’s not particularly likely that indigenous children would be at higher risk than other children. Certainly not young indigenous children. Older indigenous children, we’re not sure yet. And that may play out during the pandemic. As to whether one should sort of prophylactically separate all indigenous children, I’m not sure that that’s good policy or good mental health policy either. And will just increase anxiety and is probably unnecessary.

EFFECT ON HOSPITALS

MARK

How have hospitals been effected?

DAVID

I work in a children’s hospital and the major thing I can see is a lot of panic from different parts of the hospital who are themselves scared. Adult hospitals are already starting to get a very high workload compared with normal. Paediatric hospitals. Not so much. So and our intensive care unit may well end up taking adults. If there are so many adults needing intensive care that there aren’t enough beds for them.

When you work in healthcare, you have to be prepared to put yourself at greater risk than most people working would put themselves at. We’re at the pointy end of it. And it’s really important that we keep ourselves well and keep ourselves and able to help people, including our colleagues. Medical staff do not want to get infected, not only for their own sake, but because if I get infected, that means that everyone that’s been in contact with me in the days before I got sick has to self isolate. And that can be quite a lot of people.

So we’re limiting our contact with each other, which, as you can imagine, hand over rounds and so on, how do you do that? So we’re having virtual meetings and so on. As much as we possibly can. How do we do outpatients? People are cutting down on outpatients. How do we do surgery? Well, we have to do emergency surgery. But we’re cutting down on doing elective surgery, of course.

They do not want the disease spreading around the hospital if they can possibly help it because it just starts to create havoc there. And so there are lots of measures in place to prevent the spread, and that involves wearing personal protective equipment, PPE, we call it. And there’s a limited amount of PPE. So we’re talking about scarce resources as well and trying to work out sensible use of scarce resources.

I had to go into Ryde Hospital recently and Ryde hospital had a doctor who got sick and a patient who got sick there. And everybody had to go into isolation for two weeks for precautionary isolation in case they got the virus. And I went in as a patient to Ryde hospital briefly. And they had got elderly nurses out from retirement who’d come back to join the system. They were great fun. Great sense of humour and so on. The doctors there were tired, but they had all come in from other hospitals to cover. And so there’s a huge capacity for volunteerism and for people just pulling together in a crisis. And that’s what we’re going to be depending on. Will there be enough doctors to go round? In Italy, clearly, they have had problems. People are just exhausted. But the idea of flattening the curve is to try and protect the health system from being swamped. And so far, we seem to be doing that. That’s all I can say. It’s not a foregone conclusion. And the measures that we have introduced and that we will introduce will be to try and continue to flatten the curve, if you like.

COMPLETE SHUTDOWN

MARK

If we shut down the country for several weeks, would that be a way of solving the problem?

DAVID

First of all, that’s not absolutely clear. So people who are very, very sick shed the virus for quite some time. We know that they can shed it for weeks. So just closing the country down doesn’t mean there’s not somebody shedding the virus. There’ll be some very sick people. If you do that and they won’t get the best health care, how do you get the best health care if you’re shut down in a house? You know, in parts of the world, people are dying in their homes having not got adequate healthcare.

You could cause huge problems by shutting everything down. That does not necessarily solve the problem. And when you open up again your economy will be shot and you may still have the disease spreading. So that would be a huge step to try to take. It would be a very, very risky one. And I don’t think it would be effective.

How long are you going to do it for? Weeks? Months? There are concerns that if you do that you get hidden epidemics of domestic violence, of mental illness. You can incubate mental health problems that way. You say, “oh, go live on your own. You’ll be fine.” That’s not how society works, we’re a society that’s not geared to that very well. And the knock-on effects from doing that, which some countries have done, may take a long time to come out and to be shown.

REFUGEES

MARK

What do you think about keeping refugees in immigration detention during the pandemic?

DAVID

There are about fourteen hundred people still in immigration detention or in alternative places of detention. I think they should all be in community detention. They are a risk for getting infected themselves. They’re a risk to the guards. In fact, one guard has already gone down with COVID-19 in Brisbane.

I think also it’ll be very scary in there at the moment for them being in detention, because detention is just where things tend to spread. So I think the only humane thing is to free them. I think everything, humanity, ethics, commonsense and economics says that they should release them into the community.

MISINFORMATION

MARK

Have you seen or heard of any inaccurate information spread or misinformation spread?

DAVID

Yeah, there’s always misinformation spread and there are people who over-interpret data from other countries or over-interpret data that’s relevant to influenza, but not relevant to the coronavirus. Everybody saying you should shut schools. And yet it’s not at all clear that that would be beneficial and it might be harmful. But by and large, I would say not exactly misinformation, but misinterpretation of data or misinterpretation of the whole situation.

PROJECTION

MARK

What are your projections for the pandemic?

DAVID

At the moment, we’re getting increasing numbers of infections in Australia. The situation is concerning. I’m most worried for the elderly and for the people who are most vulnerable. And I’m worried about the mental health of the whole population.

I think we will learn from it and be better prepared probably for the next pandemic, we may learn how to make vaccines quicker. What I feel is that we’ll get through this pandemic. I know we will. The world will get through the pandemic. There’s no doubt about that. The most profound effects it’s likely to have I would think are on long-term mental health and on and on the economy. Those are my big worries.

The whole population in terms of the number of deaths, it will be some 1 to 2 percent of the world’s population possibly dying. That sounds a huge number. But when you compare it with the plague of the past, Spanish flu and so on, epidemic of 1918-1919, this is in global terms, in historical terms, a bad pandemic, but by no means anything like as bad as the ones we’ve seen before.