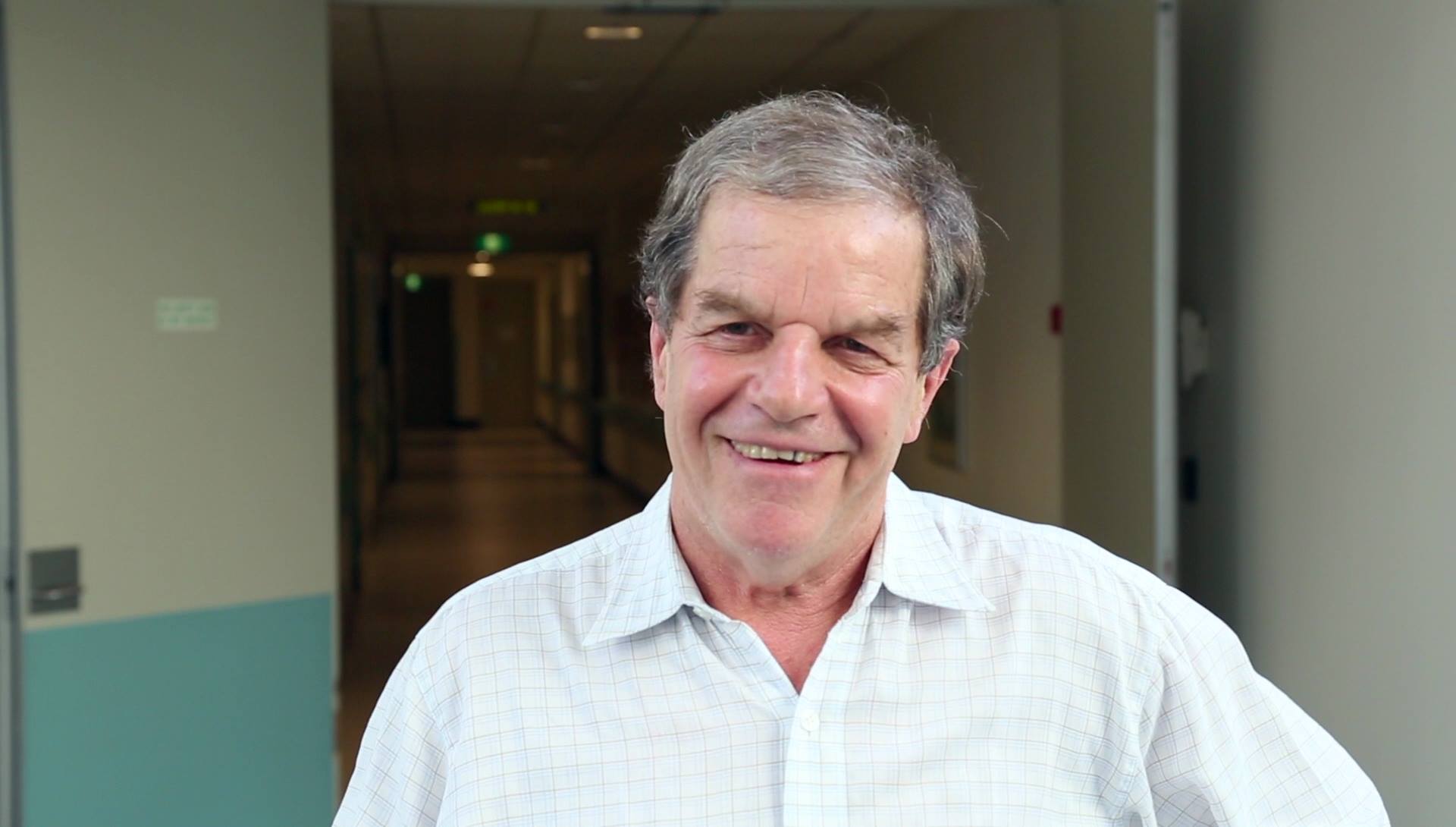

In response to the recent coronavirus pandemic, there has been an overload of information on social media and news sources. Often it’s hard to know what is good advice and what is misinformation or hysteria. I decided to speak with a trusted source to get the real deal behind the pandemic. My dad, David Isaacs, is a consultant paediatrician at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, and Clinical Professor in Paediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Sydney. He has been a member of every Australian national immunisation advisory committee for the last 25 years. He is passionate about bioethics, and has published and taught extensively on ethical aspects of immunisation.

This is a transcript of our conversation, edited to make it easier to read. The recording of the conversation is now available to listen to and will be used in a Changemakers podcast episode about the coronavirus pandemic.

*** In the last few days, my dad and I have received a positive and widespread response to this conversation, particularly from health workers and experts in the field. I was asked a number of questions in response, and I have now added more information to the article as a result.

It is important to add that this pandemic is a rapidly changing phenomenon and the information provided in this conversation was accurate to the best of David’s knowledge and the data available at the time of the interview.

Follow me on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter for regular updates on the pandemic from Professor David Isaacs.

INTRODUCTION

DAVID: My name’s David Isaacs. I’m a paediatrician – children’s doctor – and my special area is Infectious Diseases. And I suppose immunisation as well.

MARK: Didn’t you just write a book about something like this?

DAVID: Nice plug. Yes. I just wrote a book called Defeating the Ministers of Death, published by HarperCollins, about immunisations, the history of plagues and pandemics and the way we’ve developed vaccines to control them.

WHAT IS COVID-19?

DAVID: COVID-19 is the name given to the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. So C-O [stands for] corona, V is the virus and I-D is infectious disease. And it started in 2019 right at the end of the year. The name for the virus is SARS CoV2. [It’s] related to the virus that caused SARS, which was also a coronavirus. They’re sort of cousins. So you may hear them used interchangeably, but actually SARS CoV2 is the virus, COVID-19 is the disease.

It’s called a coronavirus because when you look at it under the electron microscope it’s got a crown or a halo around it [corona means crown in Latin]. We’ve known about them for 50 years as being one of the causes of a common cold in children and young adults. Occasionally they cause a bit of wheezing and occasionally a bit of pneumonia, but really not very severe infections at all.

And then suddenly, out of the blue, in 2003 came a disease called SARS, which is a severe respiratory infection with pneumonia. And that came in China and Singapore, Hong Kong, and had a very high mortality – interestingly, higher than the mortality of COVID-19 – but it didn’t spread to the rest of the world, although we were scared it would. Since then, there’s been a virus infection called MERS, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome. Now, all of those coronaviruses, SARS, MERS and the new virus, the novel coronavirus, are viruses that infect bats, don’t seem to do them much harm, and then somehow they get to humans.

Usually there’s what we call an intermediate host. So for SARS, interestingly, it was the civet, which is a mongoose-like mammal. For MERS it was camels. People got MERS when they went to the Hajj in Mecca in Saudi Arabia and they would get coughed on by camels. That was one way that we think that they were infected. In the case of SARS CoV2 or COVID 19, it seems as if the first few cases in China occurred in an open-air seafood market. They don’t just have seafood in a seafood market [in China], they have bats as well. How it got to humans we’re not quite sure.

PANDEMICS

DAVID: A pandemic is an infectious disease that spreads around the world. Pandemic just means it’s widely spread and an epidemic is spreading locally, say, within a country or within a region. There’s quite a lot [in my] book about nature being the world’s greatest terrorist and that pandemics such as the Spanish influenza at the end of the First World War killed 50 million people, more than both world wars combined. Nobody knew how to make an influenza vaccine [at the time] and it controlled itself because eventually so many of the population [had] been infected it [could] no longer spread. At that time, about 500 million of the world’s 2 billion people were infected or we were pretty sure were infected.

There are influenza pandemics about every 30 or 40 years of varying size and the difference in the size from one epidemic or one pandemic to another is how infectious the virus is and how severe it is. Flu comes around every year, changes a little bit, and our past immunity helps us a bit. And then suddenly along comes this new flu. So that’s the pandemic flu about every 30 or 40 years.

Bird flu occasionally jumps to humans, but doesn’t spread from human to human much. So it’s not proved much of a problem. And a disease becomes a problem when it can spread readily from human to human.

The swine flu is thought to have started in Mexico, although it might have been elsewhere and was caught from pigs we’re pretty sure. Interestingly, so, almost certainly, was Spanish Flu, the one in 1918. In 2009, it was called pandemic influenza. We’d been waiting for a pandemic, thinking it would come. It spread to lots of countries, but it wasn’t nearly as severe as we had feared. We now have a vaccine against the 2009 swine flu that’s part of our routine immunisation all round the world.

THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC

DAVID: Initially, it wasn’t clear whether this was going to be a pandemic, but it’s now affected almost every country in the world. So it’s definitely a pandemic. Why did SARS not become a pandemic and just became an epidemic? The answer seems to be that if you got sick with SARS, you weren’t maximally spreading the virus until you’d got quite unwell several days into the illness. So it was quite easy to identify people who were really sick, test them and then isolate them from everyone else.

The difficulty with the novel coronavirus, the one that’s causing this current pandemic, is that people seem to be much more infectious, much earlier in the illness. So they’ve really only got sniffles or even no symptoms early in the illness and they’re already passing it on to other people. So it’s much harder to control. That’s meant that people have traveled who were not feeling particularly unwell and then they’ve started spreading it in other countries, and then countries have reacted to that with a varying degree of speed. Australia actually was banning travel from Wuhan and then from China before the World Health Organization said that we should. Most other countries didn’t, so to some extent, we’re ahead of the game in Australia.

TRANSMITTING THE VIRUS

DAVID: Coronaviruses are basically respiratory viruses. You breathe them in through your nose, possibly through your mouth, and into your lungs. You can get some respiratory viruses by rubbing the virus into your eyes, which is why people wear goggles to protect themselves. It’s not thought to be swallowed. It must be something in the preparation of the bats that cause it to form droplets and you then inhale those droplets. So it’s inhaling, not ingestion, we think.

The people we know are most vulnerable are people over 80 – you might even say over 70 – but older people, and then people with what we call co-morbidities. Things like type 2 diabetes, prior severe lung disease and so on. Not asthma, but people with things like bronchiectasis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Those are the people at greatest risk.

There are some reassuring things about the virus. Pregnant women seem to be relatively mildly affected. They get it about as badly as any other woman of that age. Not worse.

Young children and newborns don’t get very sick with it. In the whole world, there’s not a child under ten who’s died from the infection. And very few who’ve got very sick from it under that age. As to why that is, nobody’s quite sure. But we think it’s because as you get older, you respond more vigorously to infections. And, although children seem to respond well enough to get over the infection, they don’t over-respond. So, older people may actually be over responding to the infection and to a certain extent, it’s their own host immune response that does some of the harm.

There are children as young as toddlers getting infected but not getting very sick. There have been a very small number of cases of newborns catching it from their mother soon after birth with no symptoms at all. But they are not getting sick. So, again, newborn infections certainly don’t seem to be a big problem.

As a paediatrician, David was predominantly speaking about young children. He later added, after a query from the public, that teenagers very occasionally have gotten very sick.

MARK: What’s the easiest way to prevent transmission?

DAVID: Find ways of avoiding droplets. We talk about wearing masks if you’re sick or avoiding other people, if you’re sick, or if you’ve got respiratory symptoms. Droplets can land on surfaces and they can be infected, contaminated for quite a while. Wipe down surfaces that might have been contaminated by someone else and wash your hands. There’s very little evidence of it spreading on clothes. So it can stay on surfaces such as [metal or plastic] for up to two or three days. But on clothes, it doesn’t stay very long.

People are terribly worried about having little alcohol sprays. They’re great if you’ve got them, but hand-washing with soap will work perfectly well. This is a virus that has an envelope around the outside of it made of fat and fats are notoriously susceptible to soap. So soap and water really work very well.

Most of the initial transmission seems to be within families. But social gatherings, you can get transmission there as well, which is why there’s increasing pressure around the world to reduce social contact with lots of people. We’re talking about physical distancing – because we don’t want to be anti-social. Staying a metre and a half apart because the droplets don’t go very far. The evidence suggests that the virus drops fairly quickly if someone coughs it out.

Outdoors there’s likely to be much less spread. It won’t spread in water. If you swim next to someone who’s got the infection and [they] cough and splutter on you, then you could get it. But it’s not under the water or through the water.

MARK: So I can go surfing?

DAVID: You can go surfing, on your own.

MARK: Why are only sick people being asked to wear masks and not everyone?

DAVID: That’s in case you run out of masks. You have limits in the amount of personal protective equipment, including masks and the best masks are expensive and in fairly limited supply. You probably don’t need it for walking around when you’re well and when you’re only coming into contact with well people.

WHAT HAPPENS IF YOU’RE INFECTED?

DAVID: If we’ve got somebody that we know is infected, we test their secretions until they’re clear and we isolate them. The virus takes two to twelve days to cook and then it’ll show itself. After two weeks, if you haven’t got sick, then you haven’t got infected. Almost certainly. If you’re infected, you can shed the virus for anything from a fairly short time up to a matter of more than two weeks. So if you’ve been very sick with the virus, you often keep the virus there for quite some time. And those people we don’t allow out of isolation until they have cleared the virus and we check them. Once they’ve cleared the virus, they are then immune and they’re not chronic shedders of the virus.

MARK: What do you do when it’s a serious case?

DAVID: If someone has COVID pneumonia, they may recover without any treatment. They may need just oxygen by a face mask. But if they get really sick, they may need to go on a ventilator machine (what the Americans call a respirator). We would usually put a tube down their trachea (windpipe) and the ventilator pumps in oxygen under pressure until their lungs recover. COVID pneumonia can take a long time to recover so you can run out of ventilators.

In Italy, they’ve actually had the ghastly situation of doctors having to decide who should and who shouldn’t be ventilated because they haven’t got enough ventilators. That is the worst decision anybody in intensive care can ever make. That is what the rest of us are trying to avoid; to be in a position where we don’t have enough ventilators. I think we should just have to be optimistic that by flattening the curve we’re not going to be in the position.

We at Sydney Health Ethics are writing about the possibility just in case.

MARK: Once you’ve become infected and you’ve recovered from that, can you then become infected again?

DAVID: Most people think that’s highly unlikely. There haven’t been re-infections that we know about. If you look at other coronaviruses, and there have been a few in the world before, re-infections are very uncommon; with the same strain they almost never occur. So we would expect, like with measles, once you’ve had it, you will never get it again. We’re not absolutely sure, but that’s what we think. [There are cases of people who relapsed after having apparently recovered, but that’s not the same as reinfection].

An addition: in mild coronavirus infections (which cause mild respiratory infections) you can get reinfections but in more serious cases such as SARS and MERS this has not been the case.

HERD IMMUNITY

MARK: Can you tell us about the idea that the British have about trying to use herd immunity?

DAVID: Herd immunity is the idea that when a certain proportion of a population is immune the virus or the disease can no longer spread in that population [because] there aren’t enough susceptible people. You can get that herd immunity by everyone having had the infection, as we just talked about with Spanish flu in 1918, or the herd immunity can be through immunising everyone. So, for example, measles can’t spread in Australia because over 95 percent of our population is immune to measles through immunising them. So if someone comes from overseas with measles, one or two unimmunised people might get infected, but it no longer spreads. We have herd immunity. Our herd is protecting the weak, if you like. So that’s the concept of herd immunity.

The UK had this idea that they could just let the population get infected and once 60 percent of the population were infected, the epidemic would be over because there would be herd immunity there and the disease wouldn’t spread anymore. The trouble with that is if you just let it spread at any rate and lose control of the spread, you actually get overwhelmed with the numbers of infected people. The UK’s population is 70 million people, 60 percent of them is 42 million people. Even with a 1 percent mortality, that’s 400,000 deaths. Currently in the UK, the mortality rate is 5 percent. So that would be an estimated 2 million deaths in the UK. So they’ve suddenly realised that way was a bad mistake and a bad suggestion, a bad miscalculation. And they’ve changed [their approach] now.

FLATTENING THE CURVE

DAVID: Flattening the curve is trying to decrease spread. If you think of the curve as being the number of people getting infected over time, if they’re getting infected very rapidly then there’s a lot of pressure on intensive care beds. If they’re getting infected more gradually over time, then the healthcare system is likely to cope much better.

You need about 60 percent of people to have been infected with the novel coronavirus before it’ll stop spreading in the population. Sixty percent sounds a heck of a lot of a population, it is, but a lot of them will have a very mild disease or be completely asymptomatic and yet have been infected and therefore be immune and not be able to pass the virus on.

What we’re trying to aim for is that we get 60 percent of the population will eventually have been infected, but they are not infected too quickly. If they get infected very quickly, as they did in Italy or in China early in the epidemic, then that overwhelms the health system and you get more deaths because the health system just can’t cope with so many people in intensive care at once.

The aim will be that it takes about six months and sufficient people in the population will have been infected to make spread much less common, if at all. The ideal would be that it would spread to the people best able to cope with it – the younger people within the community – and you would protect the most vulnerable people.

HOW TO FLATTEN THE CURVE

DAVID: Try to reduce contact between people who may have the infection and other people. We’re particularly keen to protect the elderly and the people at highest risk. They are the people who should self isolate the most.

In a pandemic, you have to work out ways that limit spread and don’t impinge too greatly on normal civil liberties. It’s a delicate balance between what’s best for the individual [and] what’s best for the country. In some parts of the world where they don’t have civil liberties in the same way that we have, it’s probably easier for the government to say we’re going to send everyone home for two weeks, you’re not allowed to speak to anyone, to touch anyone.

We’re also keen not to put in measures that might be counterproductive, making everyone work from home and be at home actually increases anxiety. There are studies showing that if you put people in social isolation because of a pandemic like SARS, that has a profound effect on their mental health. Both at the time that they’re there, but for months or even years afterwards they are more anxious than people who weren’t put in isolation. The evidence from the SARS outbreak is that it leaves people very stressed and increases post-traumatic stress disorder. Being scared of the virus has an effect on people’s mental health, and people will suffer from the fear as much as there will be some people who will die from it. So it’s not a benign thing to shut everyone away and say, just don’t talk to anyone else. It has social implications. It has mental health implications.

Those are the sort of things that we as a community have to try and deal with by helping the most vulnerable people, the people whose mental health is most at risk, and those people with preexisting health problems, including people seeking asylum and refugees, who are at particular risk.

THREATENING OUR WAY OF LIFE

MARK: In what ways does a pandemic threaten our way of life?

DAVID: I think it doesn’t just threaten our physical health, it threatens our mental health as well. There is a great deal of fear around the unknown. A new agent that you can’t see that spreads from person to person is a frightening concept. The elderly are scared about what’ll happen to them. [We’re] scared about what will happen to [our] relatives. [We’re] scared about what will happen to the economy. There are 20 year olds, 30 year olds, 40 year olds, 50 year olds dying from this infection. It is scary. The only people who can be pretty certain they are not going to die are children under 10 because there hasn’t been a single death of a child under 10. But on the other hand, there are thousands of deaths from flu every year in Australia, mainly in the elderly. We may never reach as many deaths in Australia from COVID-19 as we do from the flu every year.

Part of what governments try to do is to calm people down, say, don’t be so frightened. We’re all in this together and we’ll try and work together, have solidarity in trying to deal with it. I think we all have to find ways of coping with being a bit overwhelmed by this. It’s everywhere. It’s in all the news. It’s all the conversation is about at the moment.

MARK: Do you think social media escalates the panic?

DAVID: That’s a difficult question and I’m not sure that I can answer that. I don’t do social media very much. I think it can certainly but there’s also the potential for social media to be extremely helpful. Grandparents are using social media to talk to their grandchildren rather than seeing them face-to-face. Social media has the power to be a real force for the good, as well as potentially fuelling fears.

AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

MARK: How has our government responded to the pandemic?

DAVID: The government is seeking best advice. It’s got an expert committee that advises them every day on which measures to use. Our government has a chief medical officer, Dr. Brendan Murphy, and the government is bound to follow what he says. Brendan Murphy is a good, sensible public health physician and he immediately got round him a committee [AHPPC]. The names [of the committee members] haven’t been published because almost certainly they will be attacked on social media and it would make their lives a misery.

The AHPPC advises him every day on what they should do based on the current figures, based on what’s going on around the world and says what measures should be put in place and how much testing should be done. They are working night and day, keeping up with the literature, advising the government. Brendan Murphy takes that advice, synthesises it, makes recommendations to the government and, by and large, the government is sticking with what they are saying. The government then publishes information from the AHPPC on the Australian Government Department of Health website. That’s who I trust and I think that’s who we should all trust. They won’t make perfect decisions. Nobody can. But they’re making considered decisions based on the best evidence available to us. And that evidence is Australia-specific. It’s informed by experts all around the world. If that committee says it’s not yet time to shut the schools, that is a considered decision. It’s not a random decision based on no evidence, as some people seem to be saying out there. This is a considered decision and I trust them. And I think everyone else should trust them.

MARK: What do you make of critics who are saying things like, why haven’t we got more tests?

DAVID: We’re testing as many [people] as we can. There is a capacity. The hospital where I work, the adult hospital next door is doing fifteen hundred tests per day. The tests take four to six hours each. They’re at capacity. You’ve got to get staff to do it and staff are working much harder than they ever have before. They’re working long hours, working during the night to do testing. And then you also have to have the kits. You can’t do the test if you haven’t got the kits and everyone around the world wants the kits to do it. There’s a global shortage of tests. We’ve done over 100,000 tests of which about 0.5 percent are positive; one in every 200 tests are positive. People want to test more people, including people at lower risk of the disease. Then we won’t have enough kits for the people who are really likely to have the disease. That’s not helpful either. So you’ve got to let the experts try and make expert decisions.

We have plenty of critics. They may be doctors, they may be ex-doctors now media personalities, they may be commentators in the media, they may be the general public. They all seem to think they know better than the expert committee. I don’t think it’s helpful to be sledging government decisions at this moment. Angela Merkel made a phenomenal video in which she said, let’s all be in this together, let’s count on solidarity, let’s support each other support the weak. You just have to trust that we’re trying our best and doing as well as we can and criticising it isn’t necessarily very constructive.

MARK: Do you think there’s a space for constructive criticism?

DAVID: There should always be a space for constructive criticism, and there is the ability to do feedback, but constructive criticism is not what I’m hearing a lot of the time in the media. It’s rather judgemental, simplistic, accusatory, and it’s done by people who don’t really know.

MARK: Do you think part of the reason why sections of the media are being so negative and people are being so negative is there’s a lot of distrust in the government?

DAVID: I think that part of it is that the media likes to be sensational and that sells stories. Part of it is that there is a lack of trust. And we know that this is a government that has systematically rubbished experts in other fields like climate change.

David and I spoke about this at length after the interview. He answered these questions from a medical perspective and he believes the government is responding well to the medical advice. I suggested that they have been criticised for confusing and unsatisfactory communication, poor border control policies at airports and with cruises, among other things. He admitted this may be true, but also believed these shortcomings highlight just how unpredictable and fast-moving a pandemic can be. He advocates for solidarity.

OTHER COUNTRIES’ RESPONSES

MARK: Why were China and Singapore so effective in shutting it down?

DAVID: Both countries introduced draconian measures to control the outbreak, which would probably not be acceptable in Australia. People staying in their homes, having food delivered, not intermingling at all. The places were deserted for weeks until the infection came under control.

There are people making political mileage calling it the Chinese virus and blaming China, but I think China has done pretty well. They had some 3000 deaths in China in a short period. But since then, it’s come under control. Their epidemic lasted two months. If you think of the population of China, 1.4 billion, and they’ve had some 3,000 deaths, and Italy has already surpassed that with a population the fraction the size of China, you can see how well China coped.

I’ve heard people say Singapore was well-prepared for a pandemic, but that’s because they [had] a horrible time with SARS and they’ve enacted things to try and prevent that. That’s been vigorous quarantining of people or isolating of people and identifying people very quickly. They were very quick to realise how many tests they needed to do. Doing lots of tests, limiting travel very quickly into Singapore and, interestingly, not closing schools.

Australians would not and many parts of Europe would not accept those measures as being for the public good and would either not obey them or I think there would be huge concerns about that. Countries have different levels of democracy, different levels of social control by governments. They also have different aged populations. They have different borders. We’re an island. We’re in a lucky position to that extent and are better able to control the flow of people into the country. Some people are naturally blasé about things and go to the beach when they’re told not to. In Portugal, the day they told everyone to work from home, the beaches were completely crowded and then we did it ourselves here in Australia and Bondi Beach was completely packed.

Italy’s in a disastrous state. It would be petrifying to live in Italy at the moment, I think. They’ve already had more deaths in Italy than the whole of China and not looking like stopping any moment. That’s because they didn’t react quickly enough to the epidemic. Their mortality in Italy is about 10 percent. That’s incredibly high. The mortality in Germany and Australia is less than 0.5 percent, so 20 times lower than Italy. Thirteen of the 14 deaths in Australia have been people over 70. There was one person over 60 who died.

I think the UK and the US are heading for quite nasty outbreaks. That’s what the numbers suggest. They may have reacted in time in the UK and it won’t be as bad as Italy and Spain. But I think both countries are at risk that it’s going to be pretty bad.

If you refuse to test, as Indonesia did for a bit, funnily enough, you don’t find any cases. And of course, you can lull yourself into a false sense of security and then suddenly the epidemic is on you. People think the United States is in that position. We know that some cases in Australia came from people traveling from the United States who weren’t known to have COVID-19.

You would want a very good public health system. I think this is going to highlight how having the government responsible for your health is terribly important and I think countries that largely have private health with its inequities will find that poor people and the elderly will be at much greater risk.

MARK: Do you think the world was prepared for a pandemic?

DAVID: The world has been talking about pandemic preparedness [for decades]. The difficulty with preparing for a pandemic is that a pandemic, by its very nature, is unpredictable because each virus is different from each other one. You can try to plan for them as much as you like, but when it actually happens, the speed of spread can still cause huge problems.

VACCINES

DAVID: One of the first things that we try to do is develop a vaccine if we know how. It takes us some months. There will be a vaccine against this SARS COv2 within a certain amount of time. And then there’ll be studies to make sure that it doesn’t make things worse. Of course, the vaccines that we use routinely are ones that have turned out to be safe. Maybe in future we’ll be better at developing vaccines quicker for situations like this. We will have learned from this outbreak.

MARK: Once that comes in will it stop the pandemic?

DAVID: It depends how effective the vaccine is and it depends whether it’s necessary. So as I’ve said [for] SARS, the vaccine was never really needed because the disease disappeared and hasn’t recurred since 2003. Now, whether that will happen with this illness, we don’t know. It’s a different disease, although it’s related, and I would think we might well need a vaccine.

If there was a vaccine available now, we’d be giving it very widely. As long as we could manufacture enough of the vaccine. You would give it to the people who are the most vulnerable. The difficulty is that we do not think a vaccine will be available for 6 to 18 months. And by that time the disease may have burned itself out as SARS did. It may not, in which case we’d desperately need the vaccine and that’ll be a question of how much we can manufacture, how much it will cost, who could afford it.

ANTIVIRALS

MARK: What is an antiviral drug and can they be used?

DAVID: The way that viruses replicate is to take over the host DNA or their host nucleic acid and persuade the host to make the viral particles. It’s a parasite, if you like. It manages to manipulate hosts and to get them to do the work to make the viruses. And there are ways of interfering with that system that prevent the virus replicating in that way. Antivirals do this.

There’s one called acyclovir that’s used for chicken pox and herpes simplex virus infections. There are very effective antivirals against HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) that were developed. One of the ones that people are looking at is a drug that was developed for Ebola and turned out not to be effective in Ebola. And then people were looking at it in SARS before SARS went away. That’s a drug called remdesivir. Chloroquine (sometimes called hydroxychloroquine) is an anti-malaria drug. It is not known yet whether or not it is beneficial or harmful.

People have looked at agents that modulate your immune response, because the worry here is that this is the immune response doing some of the trouble. But we haven’t got antiviral agents known to work against coronavirus. I don’t think anyone would quite know how to develop a new antiviral that was specifically targeting coronavirus. I don’t think we have worked that out yet.

SHUTTING DOWN SCHOOLS

DAVID: There’s a great outcry saying we should have closed the schools earlier and I think our decision not to close the schools was a difficult one, but it is a considered one. It’s not a flippant one. It’s one that was made in the light of the best evidence of what’s happening in Australia.

Children [and teenagers] don’t seem to get nearly as sick with the virus if they get infected. They seem to get infected, we think, about as often as adults, but not nearly as sick. Many of them seem to be asymptomatic, even if they’re infected, and then they clear the virus and they’re immune. We don’t know if they pass it on when they’re infected and asymptomatic, but we think they’re not big spreaders of the virus. [It is possible that people with no symptoms at all can spread the virus; however, the more symptomatic you are, the more infectious you are].

There are no cases documented where an adult has caught the infection from a child. When I say documented, I mean, nobody has written up anywhere in the literature where the adult definitely got it from the child. That’s not the only infection that does that. There are other infections where children do not transmit to adults very much, if at all. Tuberculosis is one. Adults give it to children; children don’t give it to adults. Different disease, but still, it’s not unheard of that you have children not transmitting a disease. And the previous coronavirus, SARS, was another instance where children were very rarely infected or very rarely got severe disease. I couldn’t find a single report saying teachers are an occupational group that are higher risk than anyone else. That doesn’t mean they’re not. But it’s not documented. So that is why in Australia, the government’s saying, on medical advice, that closing schools would not be beneficial.

If you close down a school that has knock-on effects. Who looks after the children? What happens to the parents who should be in the workforce? Are the children likely to expose other people like grandparents? What will happen to the teachers? They then become unemployed. They may never get their jobs back.

The scientific evidence so far suggests it would be counter-intuitive to close schools. They are worried if they close schools they will take essential workers out of the work force such as health workers. In this matter, the government is acting on advice from the experts.

[The full report by the WHO joint mission is available to read. The AHPPC’s regularly released statements give excellent summaries regarding this, taking into account our local epidemiology too.]

MARK: What about families with older or immunocompromised family members?

DAVID: People who are at high risk should try and protect them[selves] as much as possible. People [with cancer] should be asking their cancer doctor because different cancer drugs immunosuppress people to a greater or lesser extent.

MARK: What about children from other vulnerable demographics such as indigenous children?

DAVID: We haven’t yet had any cases in indigenous population and obviously we’re trying to keep it out of the indigenous population, particularly in remote areas. It’s not particularly likely that indigenous children would be at higher risk than other children. Certainly not young indigenous children. Older indigenous children, we’re not sure yet, and that may play out during the pandemic. As to whether one should prophylactically separate all indigenous children, I’m not sure that that’s good policy or good mental health policy either, and will just increase anxiety and is probably unnecessary.

The reason that we don’t let children or anyone visit old people’s homes is that if the virus inadvertently gets into the old people’s home, it’s likely to spread like mad. They’re a particularly vulnerable group. It would only take one child, who is perfectly well and was asymptomatic, shedding the virus in the old people’s home to cause pandemonium there. Now, the reason that you might shut down a school is to stop it spreading among the children in case they take it home to adults and grandparents and so on. But as I say, there’s not great evidence that shutting the school actually achieves that.

EFFECT ON HOSPITALS

DAVID: Adult hospitals are already starting to get a very high workload compared with normal. Paediatric hospitals not so much. Our intensive care units may well end up taking adults if there aren’t enough beds for them.

I work in a children’s hospital and the major thing I can see is a lot of panic from different parts of the hospital who are themselves scared. They do not want the disease spreading around the hospital because it starts to create havoc. When you work in healthcare, you have to be prepared to put yourself at greater risk than most people working would put themselves at. It’s really important that we keep ourselves well and keep ourselves able to help people, including our colleagues. Medical staff do not want to get infected, not only for their own sake, but because if I get infected, that means that everyone who has been in contact with me in the days before I got sick has to self isolate and that can be quite a lot of people. So we’re limiting our contact with each other. We’re having virtual meetings. People are cutting down on outpatients. We have to do emergency surgery, but we’re cutting down on elective surgery. There are lots of measures in place to prevent the spread, and that involves wearing personal protective equipment [PPE] and there’s a limited amount of PPE. So we’re talking about sensible use of scarce resources.

I had to go into Ryde Hospital as a patient recently and the hospital had a doctor and a patient who got sick there. Everybody had to go into precautionary isolation for two weeks in case they got the virus. They had got elderly nurses out from retirement who’d come back to join the system. The doctors there were tired, but they had all come in from other hospitals to cover. So there’s a huge capacity for volunteerism and for people just pulling together in a crisis. That’s what we’re going to be depending on. The idea of flattening the curve is to try and protect the health system from being swamped and, so far, we seem to be doing that. It’s not a foregone conclusion and the measures that we have introduced and that we will introduce will be to try and continue to flatten the curve.

COMPLETE SHUTDOWN

MARK: If we just shut down the country for several weeks, would that be a way of solving the problem?

DAVID: That’s not absolutely clear. So people who are very sick shed the virus for quite some time. We know that they can shed it for weeks. Just closing the country down doesn’t mean there’s not somebody shedding the virus. There’ll be some very sick people and they won’t get the best health care. How do you get the best health care if you’re shut down in a house? You know, in parts of the world, people are dying in their homes having not got adequate healthcare.

You could cause huge problems by shutting everything down. That does not necessarily solve the problem. And when you open up again, your economy will be shot and you may still have the disease spreading. So that would be a huge step to try to take. It would be a very risky one. And I don’t even think it would be effective.

How long are you going to do it for? Weeks? Months? There are concerns that if you do that you get hidden epidemics of domestic violence, of mental illness. You can incubate mental health problems that way. You say, oh, go live on your own. You’ll be fine. That’s not how society works, we’re a society that’s not geared to that very well. And the knock on effects from doing that, which some countries have done, may take a long time to come out and to be shown.

REFUGEES

MARK: What is your take on detention for refugees?

DAVID: There are about fourteen hundred people still in immigration detention or in alternative places of detention. I think they should all be in community detention. They are a risk for getting infected themselves. In fact, one guard has already gone down with COVID-19 in Brisbane [and there have been cases in Villawood and Melbourne]. I think it’ll be very scary in there at the moment because detention is where things tend to spread. I think the only humane thing is to free them. I think humanity, ethics, commonsense and economics says that they should release them into the community.

MISINFORMATION

DAVID: There’s always misinformation spread and there are people who over-interpret data from other countries or over-interpret data that’s relevant to influenza, but not relevant to the coronavirus. By and large, I would say not exactly misinformation, but misinterpretation of data or misinterpretation of the situation.

PROJECTION

DAVID: At the moment, we’re getting increasing numbers of infections in Australia. The situation is concerning. I’m most worried for the elderly and for the people who are most vulnerable and I’m worried about the mental health of the whole population.

What I feel is that we’ll get through this pandemic. I know we will. There’s no doubt about that. I think we will learn from it and be better prepared for the next pandemic, we may learn how to make vaccines quicker. The most profound effects it’s likely to have I would think are on long-term mental health and on the economy. Those are my big worries.

When you compare it with the plague of the past, Spanish flu and so on, this is in global terms, in historical terms, a bad pandemic, but by no means anything like as bad as the ones we’ve seen before.

Follow me on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter for regular updates on the pandemic from Professor David Isaacs.

Great article – I would like to know Prof Isaacs view on anti-virals please. Is there the possibility that an anti-viral drug can be developed much faster than a vaccine that could reduce the severity of the disease such as Valtrex for shingles?

Many thanks Mark for publishing this article, David certainly is worth writing about and quoting! Have you considered a biography?

David, thank you for a clear, calm and considered article written in language that is easy to understand.

Great article, thanks Mark and Dr Isaacs!

Hi Prof Isaacs and Mark. I hope you have seen how viral your brilliant work has gone in the past 24h since I shared it on Facebook and a couple of medical groups (the medical community in particular needed to read this!). Your wisdom, experience and sensible explanations have given reassurance and relief to thousands. Thank you both so much for your wonderful work 🙏

This is a great article. Thank you. I can’t agree more…the mental health impact on our community is going to be detrimental. I can already see the impacts, as a Clinical Psychologist in private practice. I also wish that asylum seekers maybe released into community detention.

Thank you for this well balanced, informative and very calm article – Prof Isaacs is very well respected in the medical community and rightly so. I also am concerned about the longer term mental health aspects and am certainly seeing mental health issues as a GP – but I think the reasoning behind the decisions being made is sound and well considered, just as he says. This is journalism at its very best, intended to clarify and assist with understanding of the many issues involved in the pandemic and how we manage it – I will be sharing it with friends, colleagues and patients, thank you so much to both of you.

We must keep asylum seekers in community detention. I think of their mental health as much as their safety. Let’s show some humanity to these damaged people.

Thank you Professor Isaacs.

Now, if there was only a way to get this article into mainstream media, maybe stress levels could be reduced.

I think there is a couple of irresponsible and incorrect information in this article.

Children and young people do get it and whilst their symptoms may be mild, they can spread it to those who are more vulnerable. By stating that children and young people aren’t affected makes them think that they don’t have to listen to advice about isolating and social distances. As a parent of a teen this has made it very difficult to get the message through to them. This is not an old persons disease but they believe it is.

There are many reports of people who have recovered from COVID-19 getting it again. Not everyone seems to build up the antibodies. It’s a dangerous message to send to people that if you’ve had it you won’t get it again if that is not the case.

Thank you very much for this article. You note that Singapore and China had great success shutting it down albeit with draconian measures yet state that 60% of our population needs to be infected for us to get through this. I assume not 60% of Chinese or singaporeans were infected so does that just mean it could flare up there again or do they plan to keep strict measures till there is a vaccine?

Thank you for your very clear and precise comments I am wondering if the anti malaria drug would work for the people at higher risk.?

Hello Prof Isaacs and Mark. Congratulations on a very informative interview and calmed response. Well done. It is a very sensible approach to a looming crisis. Correct and timely information is crucial to prevent panic.

Regards John Pasqua

A very well explained about the concept of “Herd Immunity”. Easy-to-understand Language!

Thank you much to David and Mark for publishing this, a very timely indeed!

“You need about 60 percent of people to have been infected with the novel coronavirus before it’ll stop spreading in the population.”

What I don’t understand is if we are staying at home and not mixing with other people, how will 60% of the population become infected?

Dear Prof. Isaacs and Mark, this impressive interview has reached me here in Germany via an Australian friend and I will distribute it to everybody I know because your rationale is very convincing and your english is easily readable. I will also forward it to my friends in South Africa where I have just ‘escaped’ last minute before lockdown on 26.03. Thank you very much from a vulnerable 81 year old….

Hi Mark & David

Thank you for this excellent article.

I’m sharing it as fast as I can!

Ali xx

Fantastic. We are both very pleased to hear this. Please do pass it on.

Thanks Ali!

From my limited understanding as a writer, not a public health expert, I think that there are numerous possible ways to try to prevent the spread of the virus. Staying indoors, physically isolated, will limit the opportunity for the virus to spread rapidly which is important to protect the weakest members of society and overloading the health system. The virus may eventually die out in a localised region because it has no-one new to infect. However, it will mean that unless we have a vaccine, people will remain vulnerable to infection. Does that make sense?

Thank you!

Thank you John!

From my limited understanding as a writer, not a public health expert, I think they will maintain strict measures until there is a vaccine or some kind of treatment. Global international travel may be limited for a long period of time.

Thanks for your comments and your concerns. We have tried to accommodate your points into the transcript. You will notice that everything David says is linked to his understanding of the current evidence in the midst of a rapidly-changing and confusing pandemic.

As far as David is aware, children and teenagers are less likely to transmit the disease than adults. That’s not to say they don’t transmit the disease. Just less likely. We have now added to the text that teenagers very occasionally have gotten very sick.

Our intention is not to undermine the government’s regulations on physical distancing or to make young people feel like they are invincible. In the conversation, we actually talk about how important those measures are and how important it is to protect vulnerable members of the community. Apart from the health benefits to physical distancing stated in the article, there is the expectation amongst the community that all citizens follow the same rules.

There haven’t been reinfections that David knows about. Although, as he said in the article, he is not absolutely sure. There are cases of people who relapsed after having apparently recovered, but that’s not the same as reinfection. Please point us to any cases of re-infection that you’re aware of.

Thanks Jackie! Please do share it.

Thank you Phoebe. It’s certainly getting a positive response.

He’s using his isolation to write a memoir!

Thanks for the great question, Kirsten. His response has been added to the text.

Thanks for the question. He said it’s not known yet whether anti-malaria drugs would be harmful or beneficial. His answer is now added to the text.

Lovely to hear from you again David! I’ve followed your refugee advocacy and fully support it and now it’s been good to hear your very rational approach to the Covid-19 pandemic. I worry that development of antibodies is not as reliable as usual given the Sth KoreAn reports of reinfections.

…. from someone who has reached the age of being triaged to No Ventilator!!!

Great reading. I met you dad as a young RN in the 90s when he used to visit Bourke Hospital for clinics. Love following him still today. Can we listen to this podcast or just read it?

Cheers,

Sharon.

Thank you for a great article. I would be really interested to hear your view on the flu vaccine. Does the flu vaccine lower your immunity and make you more vunerable to getting COVID-19? Do you recommend it and if so when is the best time to get the vaccine. I have heard it lasts for 3-4 months but also up to 6 months. I would appreciate any information you have on this.

Great informed and clearly understood article many thanks for your valued time

We will be posting the podcast soon. Currently producing it.

From David: The flu vaccine does not lower immunity. It does not mean you are more likely to get COVID. On the contrary, getting two viruses at once is worse than one. You should get the flu vaccine when it becomes available around mid-April. It lasts 4-6 months at least, which will give you some protection against flu when you’re most likely to be exposed to COVID.

I have a question about the 1918 pandemic. Why did it stop? It only infected about 25% of the population, which is not enough for herd immunity. Also, what made each of the three waves of the pandemic stop after 2-3 months?

I have a question about the 1918 pandemic. Why did it stop? It only infected about 25% of the population, which is not enough for herd immunity. Also, what made each of the three waves of the pandemic stop after 2-3 months?

Influenza tends to be seasonal, so it worst in the 2-3 months of winter and drops off outside of that. In contrast, COVID-19 does not appear to be seasonal. The 25% estimate on Spanish flu was not based on strong data. Many people have only mild illness with influenza, so the number truly infected may have exceeded the 60% or so needed to stop the disease spreading.

HI Mark

Thanks for sharing your informative interview. It was very insightful and I really enjoyed hearing your father Professor David Isaacs comments.

Please pass on my appreciation to him. I was pleased to hear he was well as I worked at the Royal College of Physicians in the early 2000s in the Examinations section and he was on the Committees.

Kind regards to you both.

Amber Hall